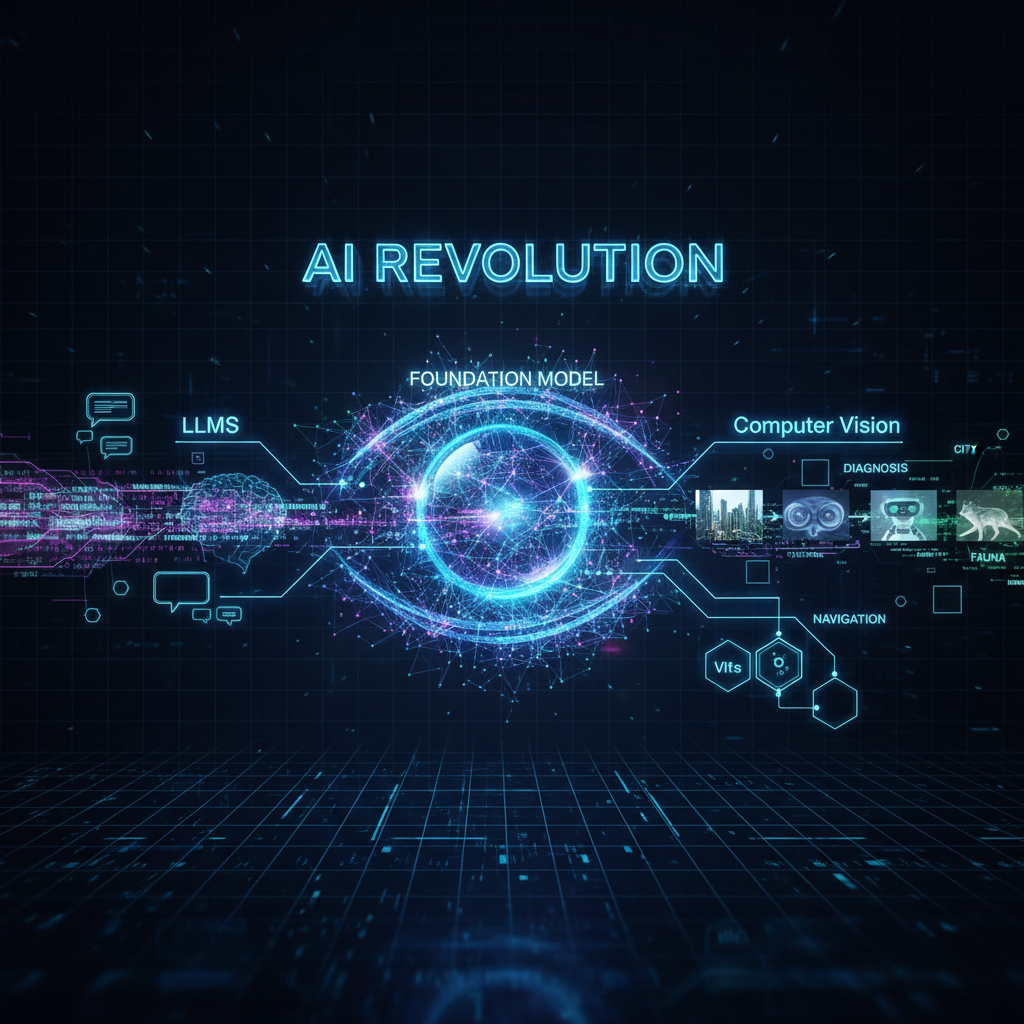

Foundation Models in Computer Vision: The Next AI Revolution After LLMs

Explore how Foundation Models, especially Vision Transformers (ViTs), are revolutionizing computer vision, mirroring the impact of LLMs in NLP. Discover their potential for unprecedented generalization and efficiency in AI applications.

The landscape of artificial intelligence is undergoing a profound transformation, echoing the seismic shifts observed in natural language processing (NLP) with the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs). A similar revolution is now sweeping through computer vision, driven by the emergence of Foundation Models (FMs). These powerful, pre-trained models, particularly Vision Transformers (ViTs) and their multimodal successors, are fundamentally reshaping how we approach visual tasks, promising unprecedented generalization, efficiency, and a new era of AI applications.

For years, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) reigned supreme in computer vision, excelling at capturing local features and hierarchical patterns. However, the Transformer architecture, initially a breakthrough in NLP for its ability to model long-range dependencies, has now proven equally, if not more, potent in the visual domain. Coupled with the power of self-supervised learning and the groundbreaking integration of multiple modalities like vision and language, foundation models are not just an evolution; they represent a paradigm shift.

This article delves into the exciting world of foundation models for computer vision, exploring the rise of Vision Transformers, the critical role of self-supervised learning, and the transformative impact of multimodal learning. We'll examine key architectures, practical applications, and the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead for AI practitioners and enthusiasts alike.

The Dawn of Vision Transformers (ViTs): A New Way to See

The core idea behind Vision Transformers is deceptively simple yet profoundly impactful: treat an image not as a 2D grid of pixels but as a sequence of discrete patches, much like words in a sentence. This allows the highly successful Transformer architecture, with its self-attention mechanism, to be directly applied to visual data.

How ViTs Work: Patching Up Images

Traditionally, CNNs process images by convolving small filters across the entire image, building up a hierarchy of features. Transformers, on the other hand, operate on sequences. To bridge this gap, ViTs perform the following steps:

- Image Patching: An input image is divided into a grid of fixed-size, non-overlapping patches (e.g., 16x16 pixels).

- Linear Embedding: Each patch is flattened into a 1D vector and then linearly projected into a higher-dimensional embedding space. This creates a sequence of patch embeddings.

- Positional Embeddings: Since Transformers are permutation-invariant (they don't inherently understand the order of elements), positional embeddings are added to the patch embeddings. This injects spatial information, telling the model where each patch originated in the original image.

- Transformer Encoder: The sequence of patch embeddings (along with a special

[CLS]token, similar to BERT, used for classification) is fed into a standard Transformer encoder. This encoder consists of multiple layers, each containing multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks. The self-attention mechanism allows each patch to "attend" to all other patches, capturing global dependencies across the entire image. - Classification Head: The output embedding corresponding to the

[CLS]token is then typically fed into a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) head for classification or other downstream tasks.

# Conceptual Pythonic representation of ViT patching

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class PatchEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

self.img_size = img_size

self.patch_size = patch_size

self.num_patches = (img_size // patch_size) ** 2

self.proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, embed_dim, kernel_size=patch_size, stride=patch_size)

def forward(self, x):

x = self.proj(x).flatten(2).transpose(1, 2) # (B, C, H, W) -> (B, embed_dim, num_patches) -> (B, num_patches, embed_dim)

return x

# Example usage

# img_size = 224, patch_size = 16, in_channels = 3, embed_dim = 768

# patch_embed = PatchEmbedding(224, 16, 3, 768)

# dummy_input = torch.randn(1, 3, 224, 224)

# patches = patch_embed(dummy_input) # patches.shape: (1, 196, 768)

# Conceptual Pythonic representation of ViT patching

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class PatchEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, img_size, patch_size, in_channels, embed_dim):

super().__init__()

self.img_size = img_size

self.patch_size = patch_size

self.num_patches = (img_size // patch_size) ** 2

self.proj = nn.Conv2d(in_channels, embed_dim, kernel_size=patch_size, stride=patch_size)

def forward(self, x):

x = self.proj(x).flatten(2).transpose(1, 2) # (B, C, H, W) -> (B, embed_dim, num_patches) -> (B, num_patches, embed_dim)

return x

# Example usage

# img_size = 224, patch_size = 16, in_channels = 3, embed_dim = 768

# patch_embed = PatchEmbedding(224, 16, 3, 768)

# dummy_input = torch.randn(1, 3, 224, 224)

# patches = patch_embed(dummy_input) # patches.shape: (1, 196, 768)

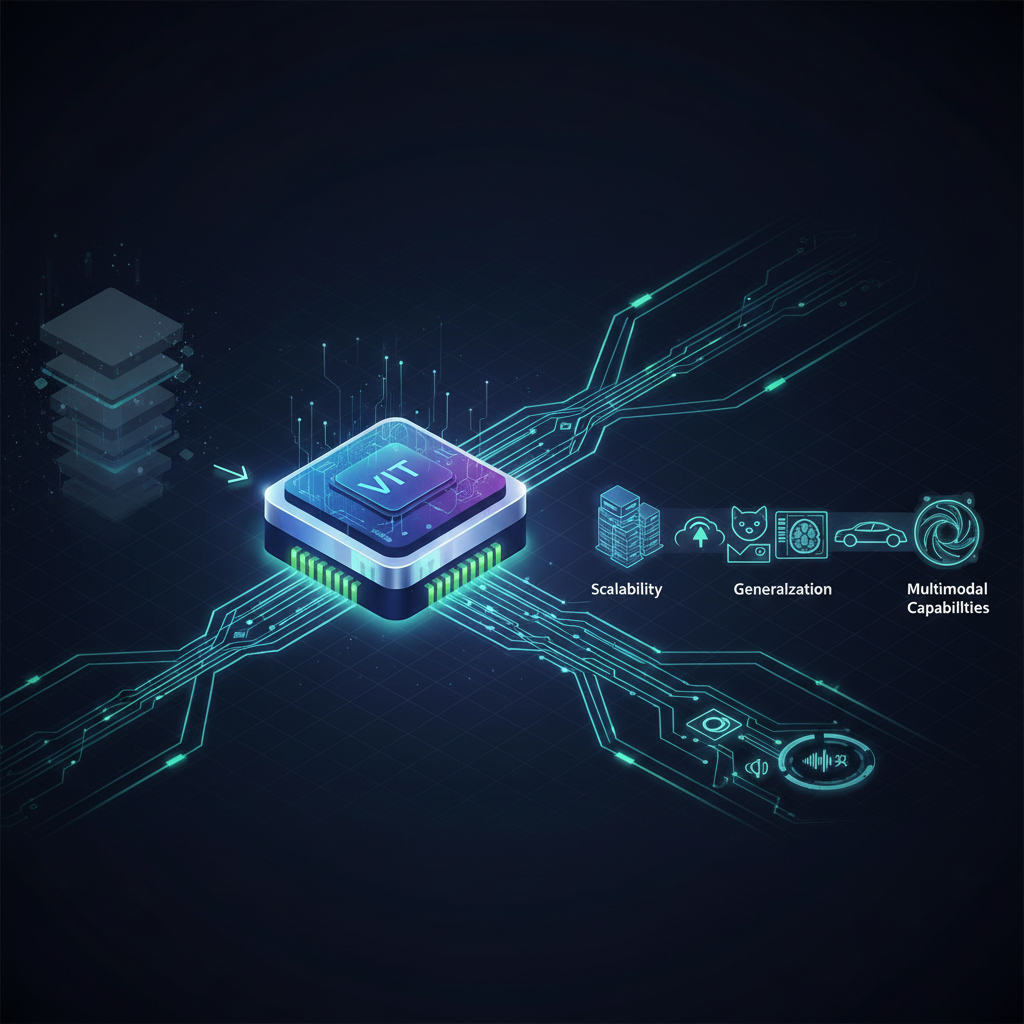

Evolution of ViTs: Addressing Practicalities

While the original ViT demonstrated impressive performance, especially when pre-trained on massive datasets like JFT-300M, it had some limitations:

- Data Hunger: ViTs initially required vast amounts of data to outperform CNNs, struggling with smaller datasets.

- Computational Cost: The global self-attention mechanism can be computationally expensive, especially for high-resolution images.

- Lack of Inductive Biases: Unlike CNNs, which inherently encode translation invariance and locality, ViTs have fewer built-in inductive biases, making them less efficient for certain tasks.

These challenges led to a wave of innovations:

- Data-efficient Image Transformers (DeiT): Introduced a "distillation token" that allows a ViT to learn from a pre-trained CNN teacher, significantly improving performance on smaller datasets without requiring massive pre-training.

- Swin Transformers: A major breakthrough that introduced a hierarchical architecture and "shifted window" attention. Instead of computing attention globally, Swin Transformers compute attention within local windows, and then shift these windows in subsequent layers. This approach achieves a linear computational complexity with respect to image size, making them highly efficient and suitable for dense prediction tasks like semantic segmentation and object detection, where CNNs previously excelled.

- Masked Autoencoders (MAE): Inspired by BERT's masked language modeling, MAE pre-trains ViTs by masking a large portion of image patches (e.g., 75%) and then reconstructing the missing pixel values. This self-supervised approach forces the model to learn rich, semantic representations of images, achieving state-of-the-art results with significantly less pre-training data compared to original ViTs.

These advancements have solidified ViTs as a dominant force, offering scalability, a global receptive field, and strong performance, especially when combined with effective pre-training strategies.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL): Unleashing the Power of Unlabeled Data

The success of foundation models hinges on their ability to learn powerful, general-purpose representations. However, acquiring and labeling massive datasets for supervised learning is incredibly expensive and time-consuming. This is where Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) comes into play.

SSL methods allow models to learn from unlabeled data by creating "pretext tasks" where the input itself provides the supervision signal. The model learns to predict some hidden or corrupted part of the input, thereby developing a rich understanding of the data's underlying structure.

Key SSL Methods for Vision:

- Contrastive Learning (e.g., SimCLR, MoCo): These methods train a model to distinguish between similar and dissimilar pairs of data points. For an image, multiple "augmented" views (e.g., cropped, rotated, color-jittered) are considered positive pairs, while other images in the batch are negative pairs. The model learns to pull positive pairs closer together in the embedding space and push negative pairs apart. This forces the model to learn features that are invariant to various augmentations, capturing robust semantic information.

- Masked Image Modeling (MIM) (e.g., MAE): As discussed with MAE, this approach involves masking out parts of an input image and training the model to reconstruct the missing information. By predicting the pixel values of masked patches, the model learns to infer context and global structure from partial observations. This is particularly effective for ViTs, as it aligns well with their patch-based processing.

- Knowledge Distillation (e.g., DINO, iBOT): These methods often involve training a "student" network to match the output of a "teacher" network, where the teacher might be a slightly different version of the student or a moving average of past student weights. DINO (self-distillation with no labels) notably showed that ViTs trained with self-supervised distillation can learn emergent properties like object segmentation without explicit supervision.

SSL has been a game-changer, enabling the training of colossal ViTs on vast, unlabeled image collections, leading to highly transferable visual features that can be fine-tuned for various downstream tasks with minimal labeled data.

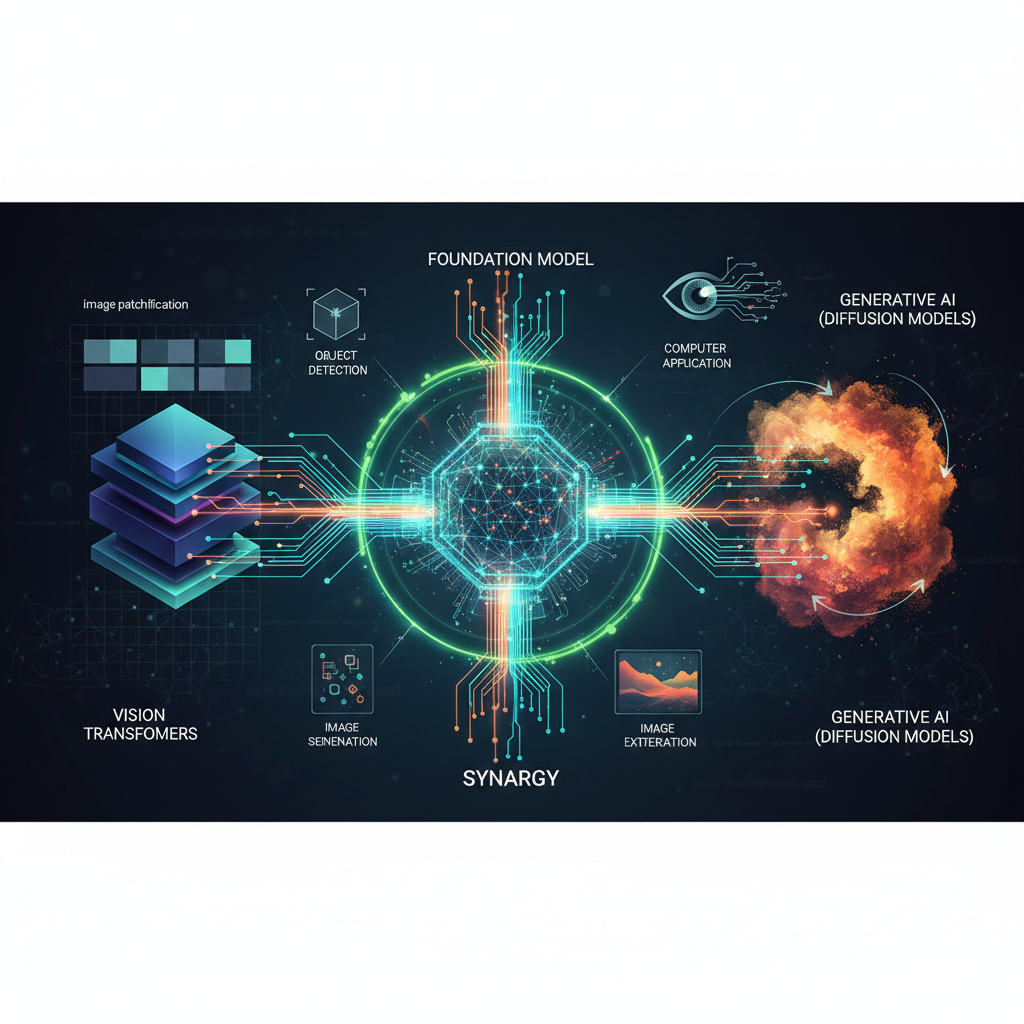

Multimodal Foundation Models: Bridging Vision and Language

Perhaps the most exciting frontier in foundation models is the integration of multiple modalities, particularly vision and language. By understanding how images relate to text descriptions, these Vision-Language Models (VLMs) unlock capabilities that were previously unimaginable.

CLIP: The Pioneer of Vision-Language Alignment

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) from OpenAI demonstrated a groundbreaking approach to learning robust, zero-shot transferable representations.

-

Mechanism: CLIP is trained on a massive dataset of 400 million image-text pairs scraped from the internet. It simultaneously trains an image encoder (a ViT or ResNet) and a text encoder (a Transformer) to produce embeddings such that matching image-text pairs have high cosine similarity, while non-matching pairs have low similarity. This is achieved through a contrastive learning objective.

# Conceptual CLIP training objective # Given N image-text pairs (I_i, T_i) # Image_Embeddings = ImageEncoder(I_1...I_N) # Text_Embeddings = TextEncoder(T_1...T_N) # Compute similarity matrix S where S_ij = cosine_similarity(Image_Embeddings_i, Text_Embeddings_j) # Loss aims to maximize S_ii (diagonal elements) and minimize S_ij for i != j# Conceptual CLIP training objective # Given N image-text pairs (I_i, T_i) # Image_Embeddings = ImageEncoder(I_1...I_N) # Text_Embeddings = TextEncoder(T_1...T_N) # Compute similarity matrix S where S_ij = cosine_similarity(Image_Embeddings_i, Text_Embeddings_j) # Loss aims to maximize S_ii (diagonal elements) and minimize S_ij for i != j -

Applications:

- Zero-shot Classification: Given an image, CLIP can classify it into novel categories by comparing the image embedding to the embeddings of various text prompts (e.g., "a photo of a cat," "a photo of a dog," "a photo of a car"). The class with the highest similarity is chosen.

- Semantic Search: Search for images using natural language queries.

- Image Generation Guidance: CLIP embeddings can be used to guide generative models (like diffusion models) to produce images that match a given text prompt.

Generative Multimodal Models: From Text to Pixels

The ability of VLMs to understand the relationship between text and images has paved the way for incredibly powerful generative AI models:

- DALL-E, DALL-E 2, Stable Diffusion: These models are at the forefront of text-to-image generation. They leverage sophisticated architectures, often combining Transformers with diffusion models, to synthesize high-quality, diverse images from textual descriptions.

- Diffusion Models: These models learn to reverse a gradual diffusion process that adds noise to an image. By iteratively denoising a random noise tensor guided by a text prompt (often via CLIP embeddings), they can generate remarkably realistic and creative images.

- GLIDE: Another text-to-image diffusion model that showcases the power of this generative paradigm.

These models are not just generating images; they are demonstrating a deep, conceptual understanding of both modalities, capable of interpreting abstract prompts, composing novel scenes, and even understanding artistic styles.

VLMs for Understanding: Beyond Generation

Beyond generating images, VLMs are also excelling at tasks that require a deeper understanding of visual content in conjunction with language:

- Visual Question Answering (VQA): Answering natural language questions about an image (e.g., "What is the person in the red shirt doing?").

- Image Captioning: Generating descriptive captions for images.

- Visual Instruction Following: Models like Flamingo integrate vision and language to follow complex instructions, often in a conversational manner.

- BLIP (Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training): A VLM that leverages a novel "captioning and filtering" strategy to generate synthetic captions for web images, improving the quality of training data and achieving state-of-the-art performance on various vision-language tasks.

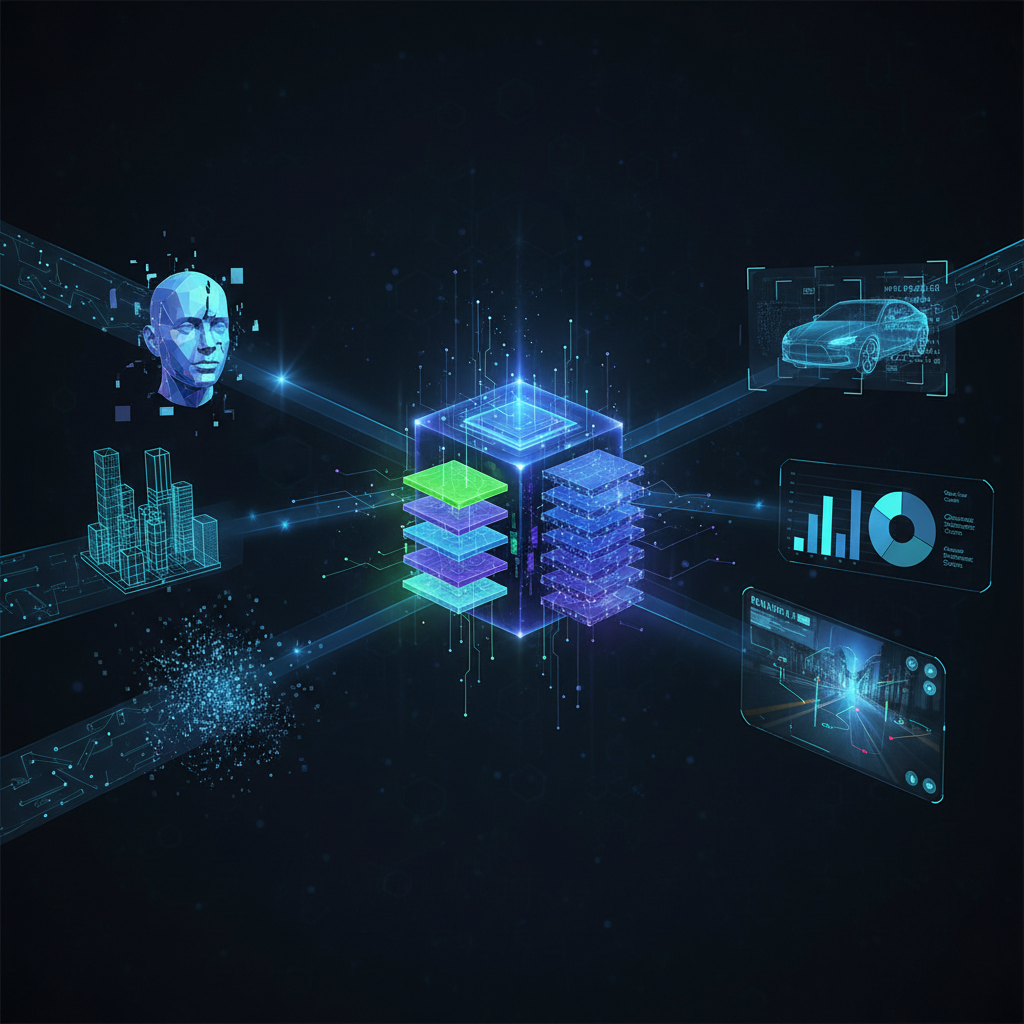

Practical Applications and Implications

The rise of foundation models for computer vision has profound practical implications across numerous industries:

- Zero-shot and Few-shot Learning: This is arguably one of the most impactful benefits. Instead of needing thousands of labeled examples for every new classification task, foundation models can classify novel categories with zero examples (using text prompts with CLIP) or with just a handful of examples (few-shot learning). This drastically reduces annotation costs and accelerates model deployment for new use cases.

- Example: A retail company can classify new product categories without extensive re-training, simply by providing text descriptions.

- Semantic Search and Content Moderation: Enhanced image retrieval capabilities. Users can search for images using natural language queries that describe concepts, styles, or even abstract ideas, rather than just keywords. For content moderation, VLMs can identify inappropriate content based on semantic understanding, not just explicit patterns.

- Robotics and Autonomous Systems: Foundation models provide more robust and generalizable perception. Robots can better understand their environment, identify objects, and interpret human instructions through multimodal input, leading to more intelligent and adaptable autonomous agents.

- Medical Imaging: While requiring careful fine-tuning and domain adaptation, foundation models can leverage their general visual intelligence to assist in specialized medical tasks, potentially reducing the burden of expert annotation for rare conditions.

- Creative Industries: Text-to-image generation is revolutionizing graphic design, advertising, and entertainment. Artists can rapidly prototype ideas, generate variations, and create unique visual content. Image editing tools are becoming more powerful, allowing users to modify images based on text prompts (e.g., "change the lighting to golden hour," "add a mustache to the person").

- Efficiency and Deployment: While training FMs is resource-intensive, their pre-trained nature means practitioners can fine-tune them on specific tasks with much less data and compute. Research is also actively focused on making these large models more efficient for deployment on edge devices through techniques like quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their immense potential, foundation models for computer vision face several challenges and open exciting avenues for future research:

- Computational Cost: Training these models requires vast computational resources (GPUs, energy), limiting access for smaller organizations and raising environmental concerns.

- Data Bias: Trained on massive, often uncurated internet datasets, foundation models can inherit and amplify biases present in the data (e.g., racial, gender, cultural stereotypes). Addressing this requires careful data curation, bias detection, and debiasing techniques.

- Interpretability and Explainability: Understanding why these complex models make certain decisions remains a significant challenge. For critical applications like medical diagnosis or autonomous driving, explainability is paramount.

- Ethical Considerations: The power of generative models raises concerns about misinformation, deepfakes, copyright issues, and the potential for misuse. Developing robust ethical guidelines and safeguards is crucial.

- Robustness and Adversarial Attacks: While powerful, these models can still be vulnerable to adversarial attacks, where small, imperceptible perturbations to input data can lead to incorrect predictions.

- Towards AGI: Multimodal foundation models are seen as a critical step towards more general and robust AI systems. Future directions include integrating even more modalities (audio, video, sensor data), developing more sophisticated reasoning capabilities, and enabling continuous learning.

- Efficiency and Democratization: Research into more efficient architectures, training methods, and deployment strategies (e.g., smaller, specialized FMs, efficient fine-tuning techniques) will be key to democratizing access to these powerful tools.

Conclusion

Foundation models are ushering in a new era for computer vision, moving beyond task-specific solutions to general-purpose intelligence. The synergy of Vision Transformers, self-supervised learning, and multimodal understanding has unlocked unprecedented capabilities in generalization, efficiency, and creativity. From zero-shot classification to text-to-image generation, these models are reshaping how we interact with and understand visual data.

For AI practitioners and enthusiasts, this is a pivotal moment. Understanding these foundational shifts is not just about staying current; it's about gaining the tools and insights to build the next generation of intelligent systems. While challenges related to bias, interpretability, and computational cost remain, the rapid pace of innovation suggests that foundation models will continue to expand the horizons of what's possible in computer vision, paving the way for more intelligent, versatile, and impactful AI applications across every domain. The future of seeing, understanding, and creating with AI is here, and it's built on foundations stronger than ever before.