Foundation Models: Reshaping the Future of Computer Vision AI

Explore how Foundation Models are revolutionizing Computer Vision, moving beyond narrow AI to create versatile, generalist, and multi-modal intelligence. Discover the paradigm shift towards adaptable visual AI.

The landscape of Artificial Intelligence is undergoing a profound transformation, particularly in the realm of Computer Vision. For decades, the dominant paradigm involved training specialized models for specific tasks – a convolutional neural network (CNN) for image classification, another for object detection, and yet another for segmentation. While incredibly effective, this approach was data-hungry, computationally intensive for each new task, and often led to "narrow AI" solutions.

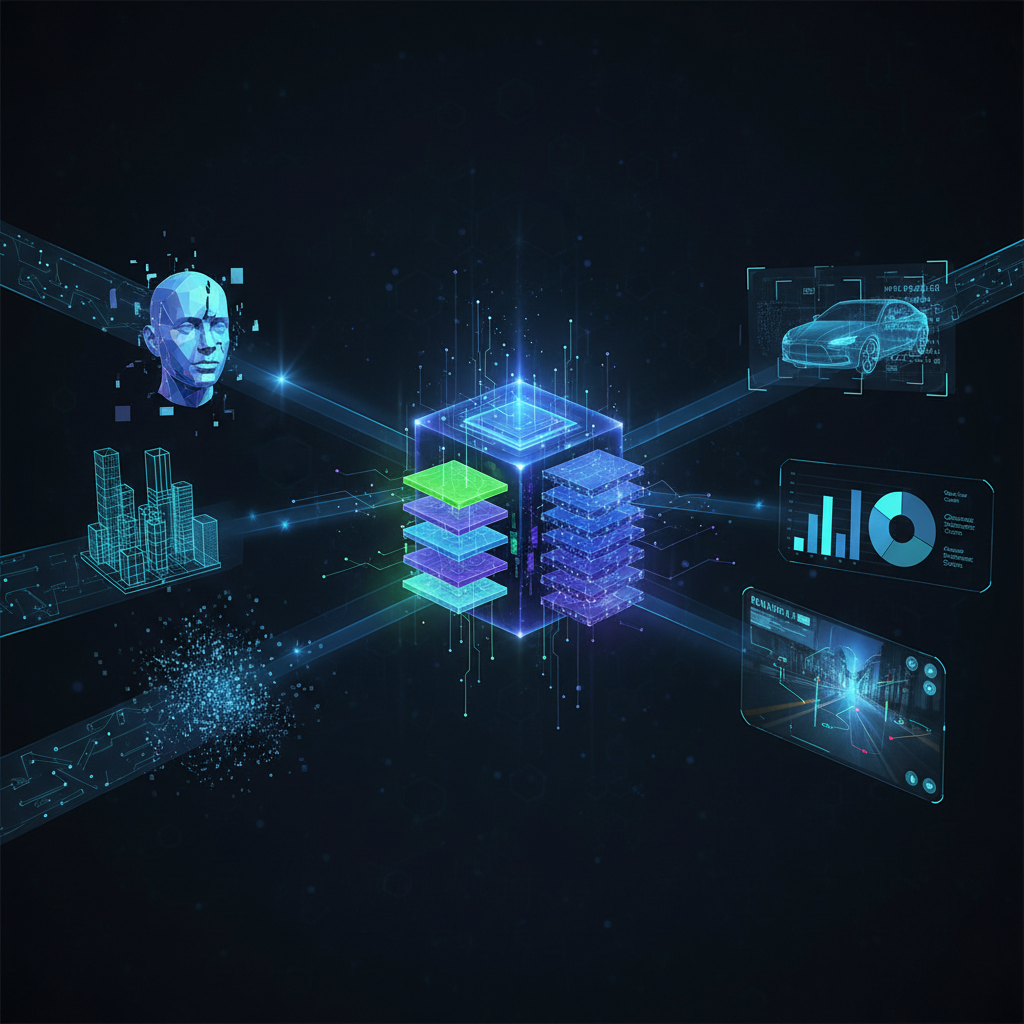

Enter Foundation Models (FMs). These large-scale, pre-trained models, often leveraging the power of Transformer architectures and self-supervised learning, are fundamentally reshaping how we interact with and develop visual AI. They represent a paradigm shift towards generalist, multi-modal intelligence, capable of understanding, generating, and reasoning about images and text simultaneously. This evolution is not just an incremental improvement; it's a leap towards more versatile, adaptable, and powerful visual AI systems that are accessible to a broader range of practitioners and enthusiasts.

What are Foundation Models in Computer Vision?

At its core, a Foundation Model is a large AI model pre-trained on a vast, diverse dataset, designed to be adaptable to a wide range of downstream tasks. The "foundation" aspect refers to their ability to serve as a base layer upon which many specific applications can be built with minimal additional training or data.

Distinction from Traditional CV Models:

- Pre-training Scale: Traditional CV models are often trained from scratch or fine-tuned from models pre-trained on ImageNet (a dataset of ~1.2 million images). FMs, in contrast, are pre-trained on datasets orders of magnitude larger, often comprising billions of image-text pairs or raw images.

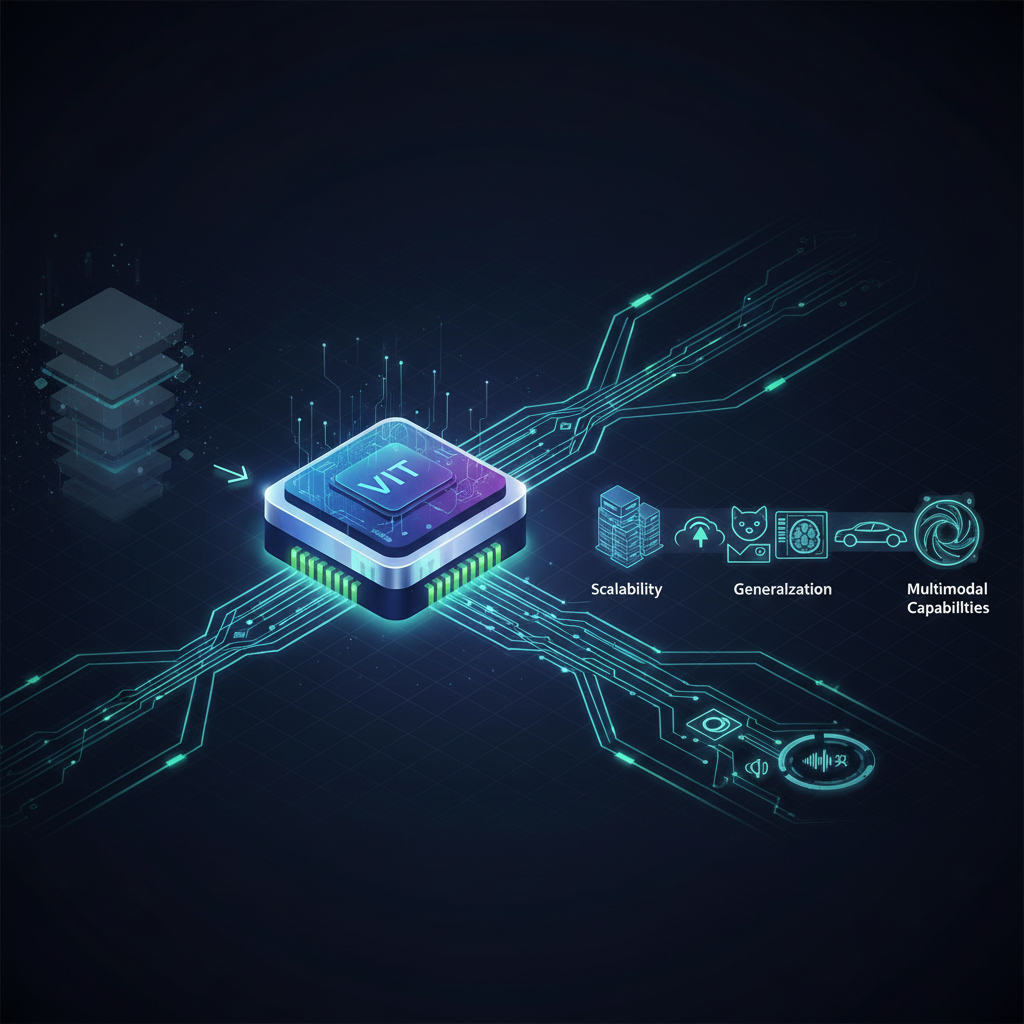

- Emergent Capabilities: Due to their scale and diverse pre-training, FMs often exhibit "emergent capabilities" – abilities not explicitly programmed or obvious from their architecture, such as zero-shot learning, complex reasoning, or multimodal understanding.

- Multi-tasking and Generalization: Instead of being specialists, FMs are generalists. They learn rich, transferable representations that allow them to perform well across a broad spectrum of tasks, even those not seen during pre-training, with little to no fine-tuning.

- Architectural Backbone: While traditional CV relied heavily on CNNs, FMs predominantly leverage Transformer architectures, which excel at capturing long-range dependencies and processing sequences, whether they are text tokens or image patches.

Key Components and Principles:

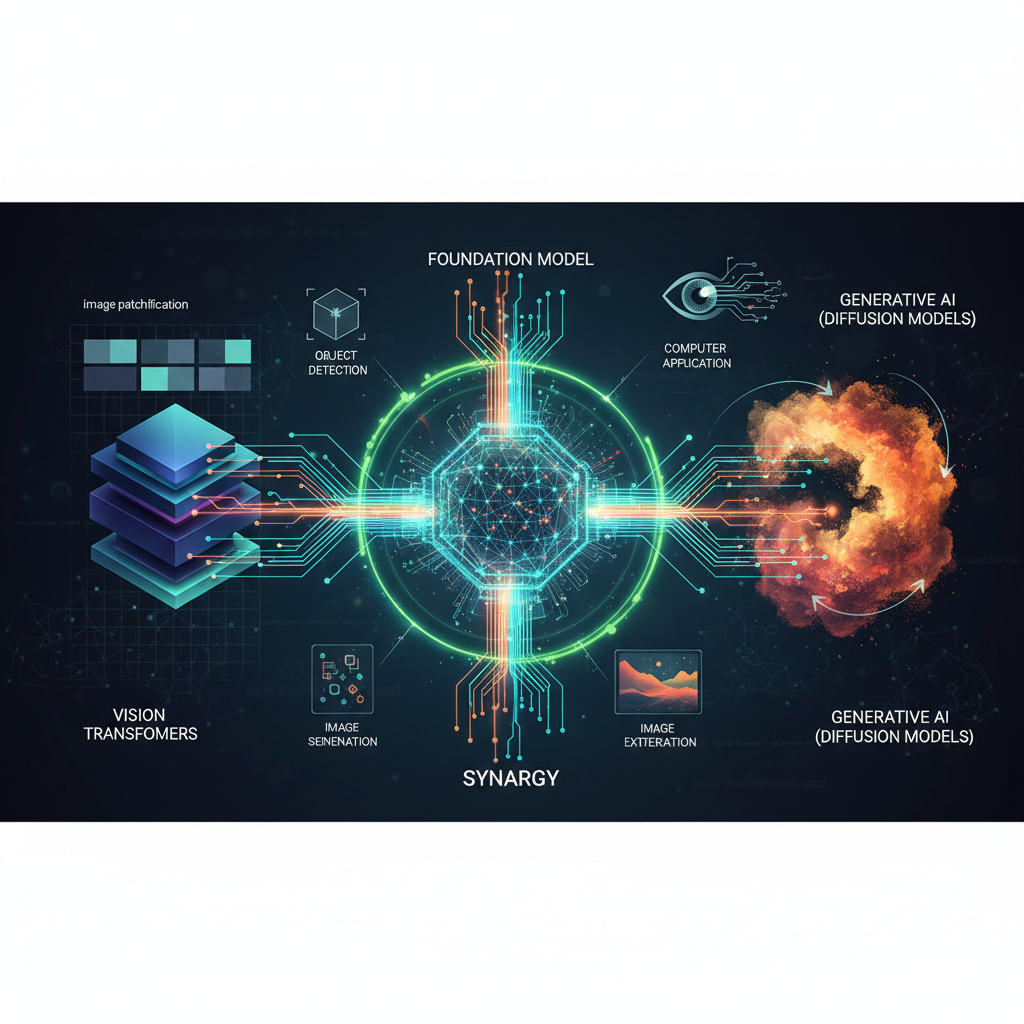

- Large Transformer Architectures: The Transformer, originally developed for natural language processing, has proven incredibly effective in vision. Models like Vision Transformers (ViT) break images into patches, treat them as sequences, and process them using self-attention mechanisms.

- Massive, Diverse Datasets: The sheer scale and diversity of pre-training data (e.g., LAION-5B, JFT-300M) are crucial. This allows FMs to learn robust, generalizable features that capture a wide array of visual concepts and their relationships.

- Self-supervised Learning (SSL): A cornerstone of FM training. Instead of relying on human-labeled data, SSL methods create supervisory signals from the data itself. Examples include:

- Masked Autoencoders (MAE): Reconstructing masked-out patches of an image.

- Contrastive Learning: Learning to distinguish between similar (positive) and dissimilar (negative) pairs of data points, often in a joint embedding space.

Vision-Language Models (VLMs) as a Core Component

Among the most impactful Foundation Models are Vision-Language Models (VLMs). These models are designed to understand and generate content across both visual and textual modalities, bridging the gap between what we see and what we describe.

How VLMs Work: Joint Embedding Spaces and Contrastive Learning

Many VLMs, especially early pioneers, operate by learning a shared, high-dimensional embedding space where semantically related images and text are positioned close to each other.

Consider Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP) from OpenAI, a seminal VLM. CLIP is trained on a massive dataset of 400 million image-text pairs. It consists of two main components: an image encoder (e.g., a ResNet or Vision Transformer) and a text encoder (e.g., a Transformer).

During training, CLIP learns to:

- Encode an image into an image embedding.

- Encode its paired text description into a text embedding.

- Maximize the cosine similarity between the correct image-text pairs.

- Minimize the similarity between incorrect (randomly sampled) image-text pairs.

This contrastive learning objective forces the model to learn highly semantic and aligned representations. The beauty of this approach is that once trained, CLIP can perform zero-shot classification: given an image, it can determine which text description (e.g., "a photo of a cat," "a photo of a dog," "a photo of a car") best matches the image, without ever being explicitly trained on those categories.

Key Architectures and Models:

- CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training): The trailblazer. Enabled zero-shot classification, content-based image retrieval, and became a crucial component for guiding text-to-image generation models.

- ALIGN (A Large-scale ImaGe-Nosearch pretraining): Google's VLM, similar to CLIP, demonstrating the scalability of contrastive learning on even larger datasets.

- Florence: Microsoft's VLM, aiming for a unified representation across various vision tasks, achieving strong performance on classification, detection, and segmentation.

- BLIP / BLIP-2 (Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training): These models advanced VLM capabilities by introducing new pre-training objectives and architectures that better integrate vision and language. BLIP-2, for instance, uses a "Querying Transformer" to bridge a frozen image encoder and a frozen large language model (LLM), enabling more sophisticated image captioning, VQA, and even conversational AI about images.

- LLaVA (Large Language and Vision Assistant): A prominent open-source VLM that connects a pre-trained visual encoder (like CLIP's ViT) with a powerful LLM (like Llama). LLaVA excels at instruction-following and visual reasoning, allowing users to ask complex questions about images in natural language.

- GPT-4V / Gemini: Proprietary, state-of-the-art multimodal models from OpenAI and Google, respectively. These models showcase advanced reasoning capabilities, often combining visual input with complex textual prompts to perform tasks like explaining diagrams, solving visual puzzles, or describing nuanced scenes. They represent the pinnacle of current multimodal AI.

Core Capabilities of VLMs:

- Zero-shot/Few-shot Classification and Object Detection: Classify objects or detect them without explicit training on those categories, by simply providing text descriptions.

- Image Captioning and Visual Question Answering (VQA): Generate descriptive captions for images or answer natural language questions about their content.

- Image Generation from Text (Text-to-Image Diffusion Models): While not VLMs themselves, models like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, and Midjourney often leverage VLMs (like CLIP) for guidance, ensuring that the generated image aligns with the textual prompt.

- Image-to-Text: The inverse of text-to-image, generating detailed descriptions from visual input.

- Visual Grounding and Referring Expression Comprehension: Locating specific objects or regions in an image based on a textual description (e.g., "the red car on the left").

Beyond VLMs: Other Foundation Model Paradigms in CV

While VLMs are a significant part of the FM landscape, other paradigms focus purely on visual understanding, often through self-supervised learning, without direct language integration during pre-training.

-

Masked Autoencoders (MAE): Developed by Meta AI, MAE is a simple yet powerful self-supervised learning approach for vision. It works by masking out a large portion of an image (e.g., 75% of patches) and then training a Vision Transformer encoder-decoder architecture to reconstruct the missing pixels. This forces the model to learn rich, semantic representations of the image content. MAE pre-trained models have achieved state-of-the-art results on various downstream tasks like image classification and object detection, demonstrating that visual understanding can be learned effectively without explicit labels or language.

- Example Use Case: A researcher can take an MAE pre-trained model and fine-tune it on a small, labeled dataset for medical image classification (e.g., detecting tumors in X-rays). The MAE's strong foundational understanding of visual patterns significantly reduces the need for massive labeled medical datasets.

-

DINO/DINOv2 (Self-Distillation with No Labels): DINO and its successor DINOv2, also from Meta AI, focus on learning dense, high-quality visual features through self-supervised learning. DINO uses a "student-teacher" architecture where a student network learns to match the output of a teacher network, with no labels required. DINOv2 further refines this by using a large, curated dataset and advanced training techniques to produce universal visual features. These features are incredibly useful for tasks requiring fine-grained spatial understanding.

- Example Use Case: An autonomous driving company can use DINOv2 features for tasks like semantic segmentation (identifying roads, cars, pedestrians pixel-by-pixel), depth estimation, or even identifying novel objects in real-time, leveraging the model's robust understanding of visual structures.

-

Segment Anything Model (SAM): Another groundbreaking FM from Meta AI, SAM is a "foundation model for segmentation." It's trained on the largest segmentation dataset ever, SA-1B (11 million images, 1.1 billion masks). SAM's unique capability is its "promptable segmentation" interface. It can segment any object in any image based on various prompts:

- Point prompts: Click on an object, and SAM segments it.

- Box prompts: Draw a bounding box, and SAM refines the segmentation.

- Text prompts: (When combined with a VLM) Describe an object, and SAM segments it.

SAM is designed for zero-shot generalization, meaning it can segment objects it has never seen before, making it incredibly versatile.

- Example Use Case: A graphic designer needs to quickly remove the background from hundreds of product images. Instead of manual selection, they can use SAM to automatically segment each product with minimal interaction, drastically speeding up their workflow. In robotics, SAM can help a robot identify and grasp novel objects in unstructured environments.

Practical Applications and Use Cases

The advent of Foundation Models has unlocked a plethora of practical applications across diverse industries:

-

E-commerce:

- Enhanced Product Search: Customers can search for products using natural language descriptions or by uploading an image of a similar item.

- Automated Product Tagging: Automatically generate accurate tags and descriptions for product listings, improving SEO and discoverability.

- Content Generation: Create unique product images (e.g., placing a product in different lifestyle settings) or marketing copy.

- Visual Recommendations: Suggest similar products based on visual features.

-

Healthcare:

- Medical Image Analysis: Assist in diagnosing diseases by identifying anomalies in X-rays, MRIs, or CT scans, potentially even in a zero-shot manner for rare conditions.

- Report Generation: Automatically generate preliminary descriptive reports for medical images, freeing up radiologists' time.

- Drug Discovery: Analyze microscopic images for cellular changes or drug efficacy.

-

Robotics and Autonomous Systems:

- Improved Perception: Robots can better understand their environment, identify objects, and navigate complex spaces.

- Natural Language Instruction Following: Operators can give robots high-level commands (e.g., "pick up the red mug on the table") without needing to program specific visual recognition routines.

- Human-Robot Interaction: Robots can interpret human gestures and visual cues.

-

Creative Industries:

- Content Creation: Artists and designers can generate images, illustrations, and textures from text prompts, accelerating creative workflows.

- Personalized Media: Dynamically generate visual content tailored to individual user preferences.

- Style Transfer and Image Editing: Apply artistic styles or perform complex edits with natural language instructions.

-

Accessibility:

- Image Description for Visually Impaired: Automatically generate detailed and nuanced descriptions of images on websites, social media, or in real-time environments, enhancing accessibility.

- Sign Language Translation: Potentially translate sign language into text or speech.

-

Security & Surveillance:

- Anomaly Detection: Identify unusual activities or objects in surveillance footage that deviate from learned normal patterns.

- Complex Event Understanding: Go beyond simple object detection to understand sequences of events (e.g., "someone leaving a package unattended").

-

Data Annotation and MLOps:

- Automated Labeling: Significantly speed up and automate the creation of training datasets by using FMs for pre-labeling or interactive labeling (e.g., SAM for segmentation).

- Data Curation: Identify and filter low-quality data or synthesize new data for training.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their remarkable capabilities, Foundation Models in Computer Vision present several challenges and open avenues for future research and development.

-

Computational Cost:

- Training: Pre-training FMs requires enormous computational resources (thousands of GPUs for weeks or months) and vast amounts of energy, making it accessible to only a few large organizations.

- Deployment: Even inference with these large models can be computationally expensive, limiting their deployment on edge devices or in latency-sensitive applications.

- Future Direction: Research into model compression (quantization, pruning), efficient architectures, and specialized hardware will be crucial for democratizing access.

-

Data Bias and Fairness:

- FMs are trained on internet-scale datasets, which inevitably reflect societal biases present in the data. This can lead to models that perform poorly for certain demographics, perpetuate stereotypes, or generate harmful content.

- Future Direction: Developing robust methods for bias detection, mitigation, and fair data curation, along with responsible model governance.

-

Interpretability and Explainability:

- Understanding why a VLM makes a particular decision or generates a specific output can be challenging due to their complexity. This is critical in high-stakes applications like healthcare or autonomous driving.

- Future Direction: Advancements in explainable AI (XAI) techniques tailored for multimodal Transformers, allowing practitioners to gain insights into model reasoning.

-

Hallucinations and Factual Accuracy:

- Especially in generative models, FMs can "hallucinate" details or generate content that appears plausible but is factually incorrect or nonsensical.

- Future Direction: Improving grounding mechanisms, integrating knowledge bases, and developing better evaluation metrics for factual consistency.

-

Safety and Misuse:

- The power of FMs can be misused for generating deepfakes, misinformation, or harmful content.

- Future Direction: Developing robust safety filters, watermarking techniques for generated content, and ethical guidelines for deployment.

-

Efficiency and Democratization:

- The high cost and complexity mean that most organizations cannot train FMs from scratch. While fine-tuning is easier, it still requires resources.

- Future Direction: Creating smaller, more efficient FMs; developing better techniques for few-shot and zero-shot adaptation; and fostering open-source initiatives to make these models more widely available.

-

Embodied AI:

- Integrating FMs into agents that interact with the physical world (e.g., robots) is a major frontier. This involves learning from sensory input, performing actions, and adapting to dynamic environments.

- Future Direction: Research into multimodal reinforcement learning, sim-to-real transfer, and robust perception-action loops.

-

Long-Context Visual Understanding:

- Current FMs often process individual images or short video clips. Understanding and reasoning over long sequences of visual data (e.g., entire movies, continuous surveillance footage) remains a challenge.

- Future Direction: Developing architectures and training methods capable of maintaining long-term visual memory and reasoning over extended temporal contexts.

Conclusion

Foundation Models are undeniably ushering in a new era for Computer Vision. By moving beyond task-specific models to generalist, multi-modal systems, they are democratizing access to powerful AI capabilities, reducing data requirements, and unlocking novel applications that were once the stuff of science fiction. From zero-shot image classification with CLIP to universal segmentation with SAM, and instruction-following visual assistants like LLaVA and GPT-4V, the pace of innovation is breathtaking.

However, this revolution comes with its own set of responsibilities. Addressing the challenges of computational cost, bias, interpretability, and safety will be paramount to realizing the full, ethical potential of these transformative technologies. As practitioners and enthusiasts, understanding the underlying principles, capabilities, and limitations of Foundation Models is no longer optional – it's essential for navigating and shaping the future of visual AI. The journey towards truly generalist visual intelligence has just begun, and it promises to be one of the most exciting frontiers in artificial intelligence.