Foundation Models: The Paradigm Shift Revolutionizing Computer Vision

Foundation Models (FMs), initially popularised by LLMs, are now transforming computer vision. This blog post explores how these large, pre-trained, general-purpose models are democratizing advanced visual AI and unlocking unprecedented applications, marking the biggest paradigm shift since deep learning.

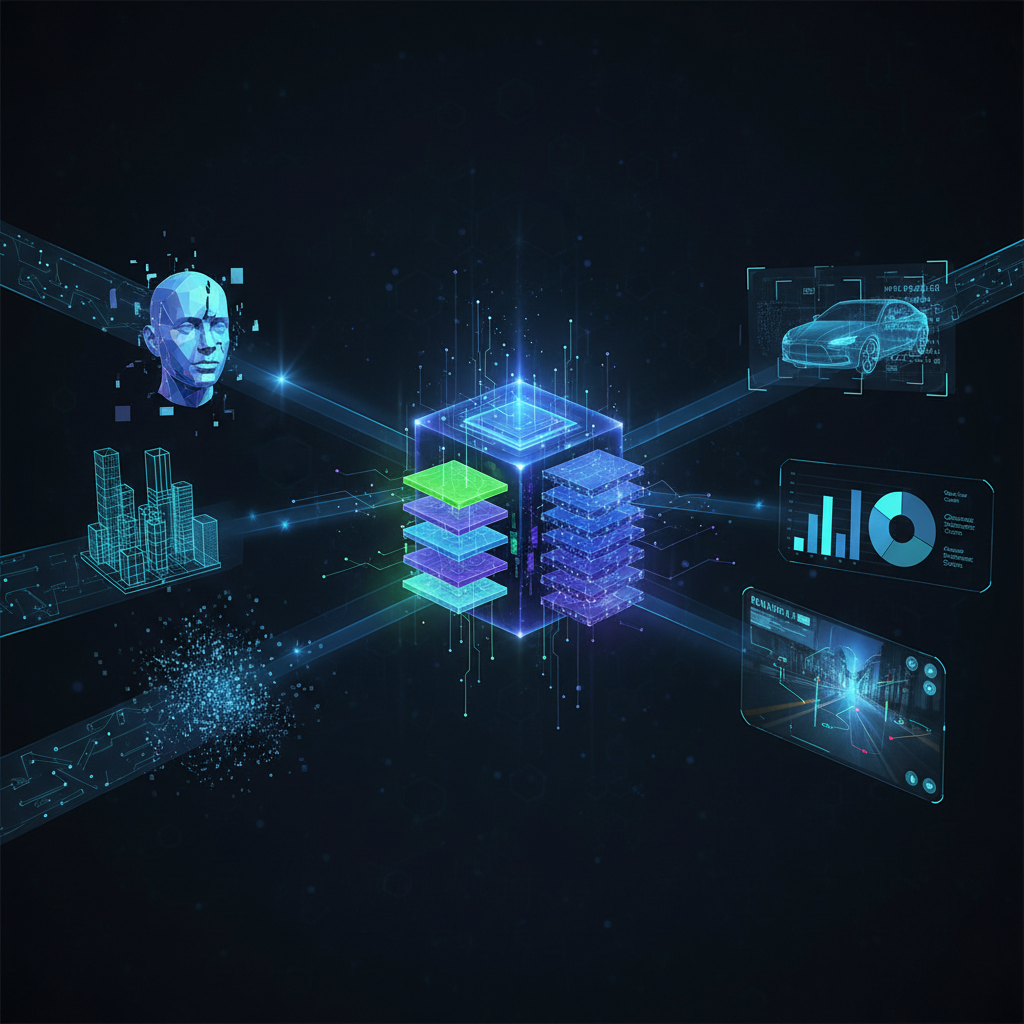

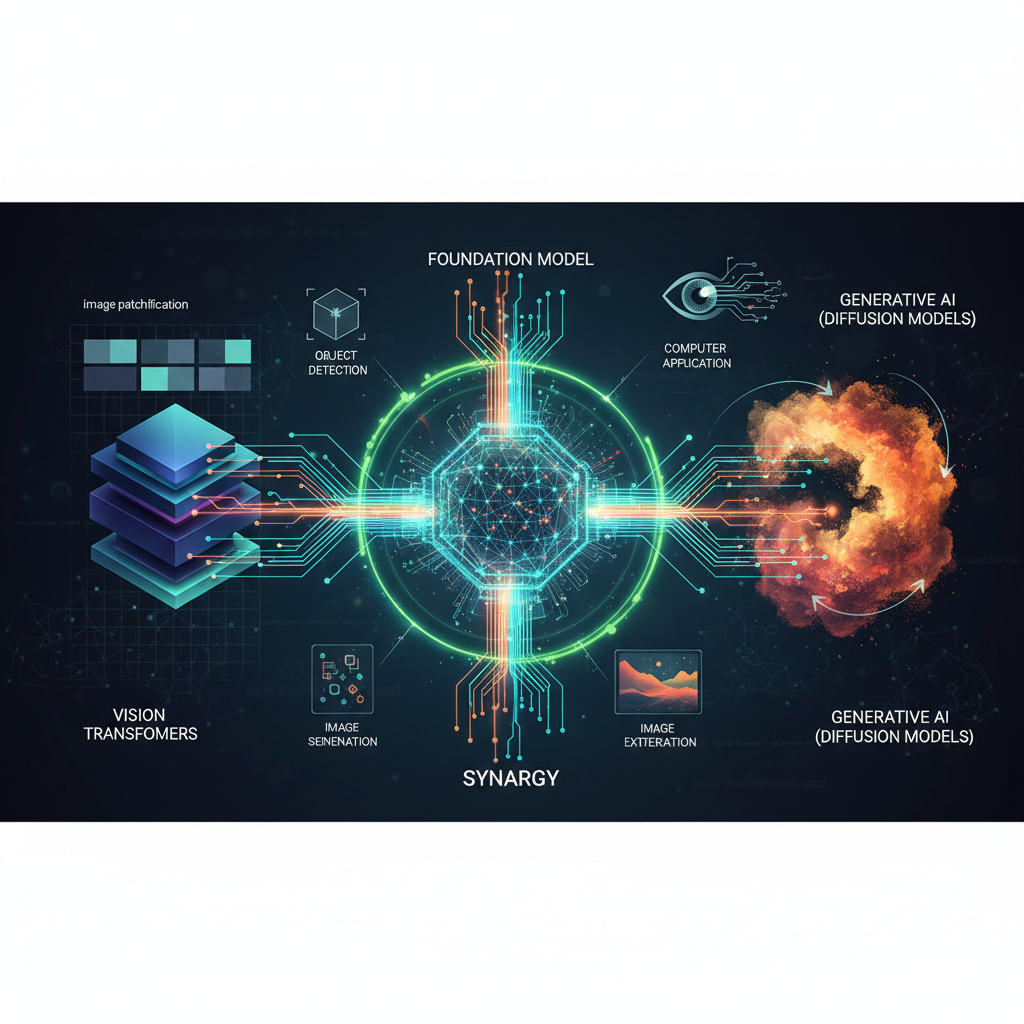

The landscape of artificial intelligence is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the emergence of "Foundation Models" (FMs). Initially popularized by large language models (LLMs) like GPT-3 and GPT-4, this paradigm shift is now revolutionizing computer vision. We are moving beyond task-specific models, meticulously crafted for a single purpose, towards large, pre-trained, general-purpose models capable of adapting to a multitude of downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning or even zero-shot capabilities. This represents arguably the biggest paradigm shift in computer vision since the advent of deep learning, promising to democratize advanced visual AI and unlock unprecedented applications.

The Dawn of General-Purpose Visual Intelligence

For years, computer vision relied heavily on models trained for specific tasks – an image classifier for cats and dogs, an object detector for cars, a segmenter for medical images. Each new task often required a new model, extensive data collection, and laborious annotation. Foundation Models challenge this status quo by learning rich, general-purpose representations from vast amounts of diverse data, allowing them to be highly adaptable.

This shift is fueled by several key developments:

- Architectural Innovations: The rise of Vision Transformers (ViTs) and their variants.

- Advanced Training Paradigms: Self-supervised and contrastive learning techniques.

- Massive Datasets: The availability of colossal, diverse datasets for pre-training.

- Multimodal Integration: The groundbreaking fusion of vision and language.

Let's delve into these pillars that underpin the rise of general-purpose visual intelligence.

Architectural Innovations: From CNNs to Transformers

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been the backbone of computer vision for nearly a decade, excelling at capturing local spatial hierarchies. However, their inductive biases (like translation equivariance and locality) can limit their ability to model long-range dependencies effectively. This is where Transformers, originally designed for natural language processing, step in.

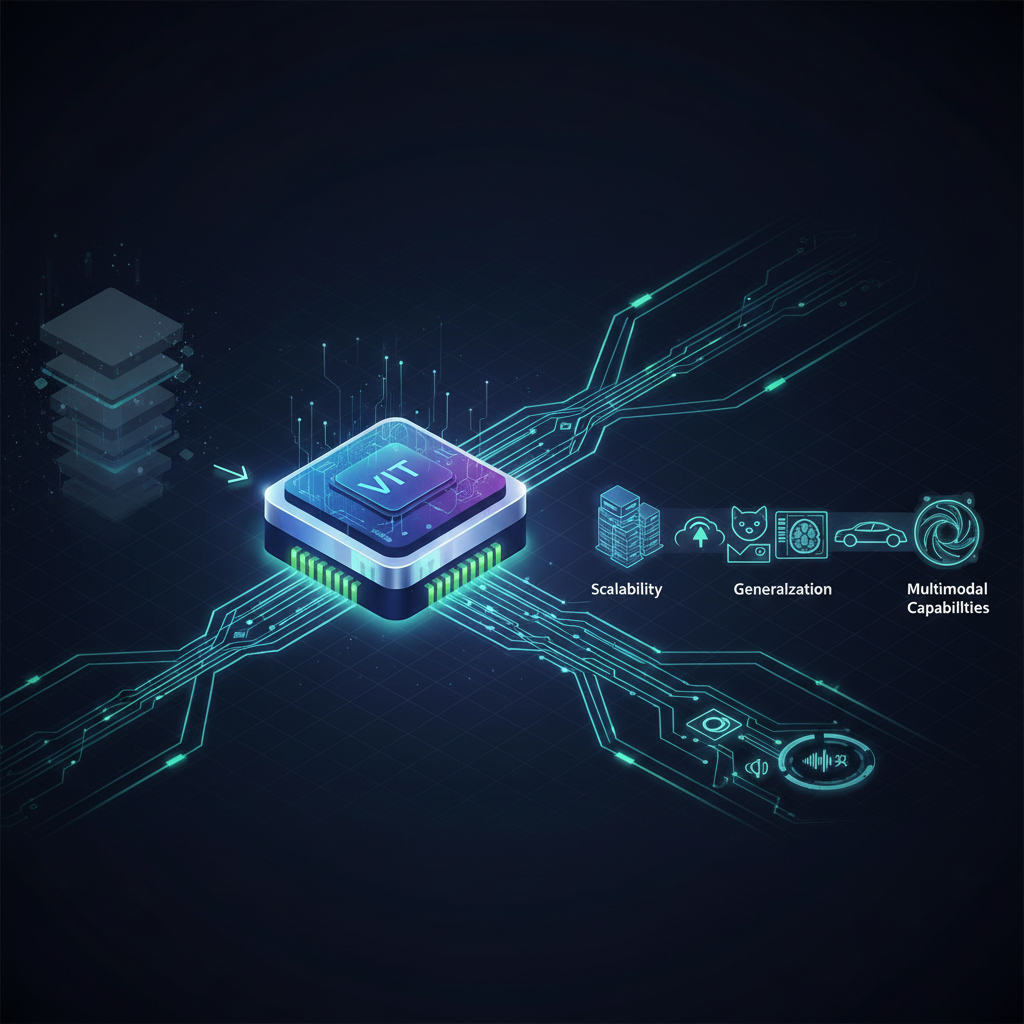

Vision Transformers (ViTs)

The seminal "An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale" paper introduced Vision Transformers (ViTs), demonstrating that a pure Transformer applied directly to sequences of image patches could achieve state-of-the-art results on image classification tasks, especially when pre-trained on large datasets.

How ViTs Work:

- Patch Embedding: An input image is divided into a grid of fixed-size non-overlapping patches (e.g., 16x16 pixels). Each patch is then flattened into a vector.

- Linear Projection: These flattened patches are linearly projected to a higher-dimensional embedding space.

- Positional Embeddings: To retain spatial information, learnable positional embeddings are added to the patch embeddings.

- Transformer Encoder: The sequence of patch embeddings (plus a learnable

[CLS]token, similar to BERT, used for classification) is fed into a standard Transformer encoder, consisting of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward layers. - Classification Head: The output corresponding to the

[CLS]token is passed through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) head for classification.

Advantages over CNNs:

- Global Receptive Field: Self-attention allows ViTs to capture long-range dependencies across the entire image from the very first layer, unlike CNNs which build up global context through successive layers.

- Scalability: ViTs scale remarkably well with data and model size, often outperforming CNNs when trained on massive datasets.

- Flexibility: The patch-based approach makes ViTs highly flexible for various vision tasks beyond classification.

Popular ViT Variants

While vanilla ViTs perform well, their computational cost can be high, especially for high-resolution images. This has led to numerous innovations:

- Swin Transformers: Introduce a hierarchical design and "shifted windows" to limit self-attention computation to non-overlapping local windows, while still allowing cross-window connections. This makes Swin Transformers more efficient and suitable for dense prediction tasks like object detection and segmentation.

- Masked Autoencoders (MAE): A self-supervised learning approach where a large portion of image patches are masked, and the model is trained to reconstruct the missing pixels. This forces the model to learn meaningful representations of the visible patches.

- DINO/DINOv2: Self-supervised methods that learn powerful visual features by training a student network to match the output of a teacher network, using techniques like self-distillation with no labels. DINOv2 further scales this by using massive, curated datasets and advanced training techniques, producing highly generalizable features.

Hybrid Architectures

Some models combine the strengths of CNNs and Transformers. For instance, a CNN backbone might extract initial features, which are then processed by Transformer layers to capture global context. This leverages the local feature extraction prowess of CNNs with the global reasoning capabilities of Transformers.

Training Paradigms: Learning Without Labels

The success of Foundation Models hinges on their ability to learn from enormous amounts of data. Manually annotating such datasets is impractical, making self-supervised learning (SSL) a critical component. SSL allows models to learn rich representations by creating "pretext tasks" from the data itself, without requiring human labels.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL)

SSL methods enable models to learn powerful visual features by solving tasks where the labels are generated automatically from the data itself.

-

Masked Image Modeling (MIM): As seen with MAE, the model predicts masked parts of an image (e.g., pixels, feature tokens). This forces the model to understand the context and structure of images.

python# Conceptual MAE training loop snippet (simplified) import torch import torch.nn as nn class MAEModel(nn.Module): def __init__(self, encoder, decoder): super().__init__() self.encoder = encoder self.decoder = decoder def forward(self, images, mask_ratio=0.75): # 1. Divide image into patches # 2. Randomly mask a percentage of patches # 3. Encode visible patches latent_representation, visible_indices, masked_indices = self.encoder(images, mask_ratio) # 4. Decode latent representation to reconstruct masked patches reconstructed_patches = self.decoder(latent_representation, masked_indices) return reconstructed_patches, masked_indices # Training: # for batch in dataloader: # reconstructed, masked_indices = model(batch_images) # loss = criterion(reconstructed, original_masked_patches) # Compare with ground truth # loss.backward() # optimizer.step()# Conceptual MAE training loop snippet (simplified) import torch import torch.nn as nn class MAEModel(nn.Module): def __init__(self, encoder, decoder): super().__init__() self.encoder = encoder self.decoder = decoder def forward(self, images, mask_ratio=0.75): # 1. Divide image into patches # 2. Randomly mask a percentage of patches # 3. Encode visible patches latent_representation, visible_indices, masked_indices = self.encoder(images, mask_ratio) # 4. Decode latent representation to reconstruct masked patches reconstructed_patches = self.decoder(latent_representation, masked_indices) return reconstructed_patches, masked_indices # Training: # for batch in dataloader: # reconstructed, masked_indices = model(batch_images) # loss = criterion(reconstructed, original_masked_patches) # Compare with ground truth # loss.backward() # optimizer.step() -

Contrastive Learning (SimCLR, MoCo): These methods train models to bring "positive pairs" (different augmented views of the same image) closer in the embedding space, while pushing "negative pairs" (views of different images) further apart. This teaches the model to identify semantically similar content despite variations in appearance.

python# Conceptual Contrastive Learning (SimCLR-like) snippet # for batch in dataloader: # img1, img2 = augment(batch_images) # Two augmented views of each image # # z1 = encoder(img1) # Get embeddings # z2 = encoder(img2) # # # Compute similarity scores (e.g., cosine similarity) # # Loss function (NT-Xent loss) pushes z1, z2 of same image closer # # and pushes z1, z2 of different images further apart. # loss = calculate_nt_xent_loss(z1, z2) # loss.backward() # optimizer.step()# Conceptual Contrastive Learning (SimCLR-like) snippet # for batch in dataloader: # img1, img2 = augment(batch_images) # Two augmented views of each image # # z1 = encoder(img1) # Get embeddings # z2 = encoder(img2) # # # Compute similarity scores (e.g., cosine similarity) # # Loss function (NT-Xent loss) pushes z1, z2 of same image closer # # and pushes z1, z2 of different images further apart. # loss = calculate_nt_xent_loss(z1, z2) # loss.backward() # optimizer.step() -

DINO/DINOv2: These methods leverage self-distillation. A "student" network learns by matching the output of a "teacher" network. The teacher network is often a momentum-updated version of the student, providing stable targets. This approach is particularly effective at learning dense, high-quality features without explicit contrastive pairs, leading to excellent performance in downstream tasks.

Large-Scale Pre-training

The sheer scale of data is another crucial factor. Foundation Models are pre-trained on datasets containing billions of images, often combined with text. Examples include:

- JFT-300M: A proprietary dataset of 300 million images used by Google.

- LAION-5B: A publicly available dataset of 5.85 billion CLIP-filtered image-text pairs, enabling research into massive multimodal models.

This massive pre-training allows models to learn incredibly rich and generalizable representations of the visual world, encompassing a vast array of objects, scenes, and concepts.

Multimodal Foundation Models: Bridging Vision and Language

Perhaps the most exciting frontier is the integration of vision and language. These multimodal models bridge the semantic gap between pixels and human understanding, enabling powerful new applications that were previously impossible.

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training)

Developed by OpenAI, CLIP is a groundbreaking model that learns to associate images with text descriptions. It's trained on 400 million image-text pairs from the internet.

Architecture and Training: CLIP consists of two main components:

- Image Encoder: A Vision Transformer (or ResNet) that processes images.

- Text Encoder: A Transformer that processes text.

During training, CLIP learns to predict which text snippet from a batch of text corresponds to which image from a batch of images. It does this by maximizing the cosine similarity between the embeddings of correct image-text pairs and minimizing it for incorrect pairs.

Applications:

- Zero-Shot Classification: CLIP can classify images into categories it has never explicitly seen during training. You simply provide text descriptions (e.g., "a photo of a cat," "a photo of a dog") and CLIP will tell you which one best matches the image.

- Image Retrieval: Given a text query, CLIP can find the most relevant images, or vice-versa.

- Guiding Other Models: CLIP's robust understanding of image-text alignment can be used to guide image generation models (like DALL-E) or image editing tasks.

Diffusion Models (e.g., Stable Diffusion, DALL-E 2)

Diffusion models have revolutionized generative AI, particularly in text-to-image synthesis. They work by learning to reverse a diffusion process that gradually adds noise to an image until it becomes pure noise.

Underlying Principles (Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models - DDPMs):

- Forward Diffusion: A Markov chain gradually adds Gaussian noise to an image over several steps, transforming it into pure noise.

- Reverse Diffusion (Generation): A neural network (often a U-Net) is trained to predict the noise added at each step, effectively learning to reverse the diffusion process. By starting with random noise and iteratively removing the predicted noise, the model generates a coherent image.

- Conditional Generation: For text-to-image, the reverse process is conditioned on a text embedding (e.g., from CLIP), guiding the generation towards the desired concept.

Impact on Creative AI: Models like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2 have democratized image creation, allowing anyone to generate high-quality, diverse images from simple text prompts. This has profound implications for art, design, advertising, and content creation.

Other Vision-Language Models

- Flamingo (DeepMind): A "perceiver-style" architecture that efficiently processes interleaved sequences of images and text, enabling few-shot learning for a wide range of vision-language tasks.

- CoCa (Contrastive Captioners): Combines contrastive learning with image captioning, achieving strong performance in both image-text retrieval and generative captioning.

Adaptation and Deployment: Making FMs Practical

While powerful, Foundation Models are often massive. Efficient adaptation and deployment strategies are crucial for real-world applications.

Fine-tuning Strategies

- Full Fine-tuning: The entire pre-trained model is trained further on a smaller, task-specific dataset. This is effective but computationally expensive and requires significant data.

- Parameter-Efficient Fine-tuning (PEFT): Methods like LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) freeze most of the pre-trained model's weights and inject small, trainable matrices into the Transformer layers. This drastically reduces the number of trainable parameters, making fine-tuning faster and more memory-efficient.

Prompt Engineering for Vision Models

Similar to LLMs, the way we "prompt" multimodal vision models can significantly influence their output. For CLIP, carefully crafted text prompts can improve zero-shot classification accuracy. For diffusion models, detailed and creative text prompts are essential for generating specific and high-quality images.

# Example of a prompt for a diffusion model

"A hyperrealistic photograph of a futuristic city at sunset, neon lights reflecting on wet streets, flying cars, cyberpunk aesthetic, highly detailed, cinematic lighting, 8k"

# Example of a prompt for a diffusion model

"A hyperrealistic photograph of a futuristic city at sunset, neon lights reflecting on wet streets, flying cars, cyberpunk aesthetic, highly detailed, cinematic lighting, 8k"

Efficiency and Optimization

Deploying large FMs on edge devices or with limited resources requires optimization techniques:

- Model Distillation: A smaller "student" model is trained to mimic the behavior of a larger "teacher" model, often achieving comparable performance with fewer parameters.

- Quantization: Reducing the precision of model weights (e.g., from 32-bit floats to 8-bit integers) to reduce memory footprint and speed up inference.

- Sparsity/Pruning: Removing redundant connections or weights from the network without significant performance degradation.

- Hardware Acceleration: Utilizing specialized hardware like GPUs, TPUs, and custom AI accelerators.

Practical Applications and Use Cases

The impact of Foundation Models in computer vision is far-reaching:

- Reduced Annotation Burden: Practitioners can leverage pre-trained FMs and fine-tune them with much smaller, task-specific datasets, drastically cutting down on annotation costs and time.

- Zero-Shot & Few-Shot Learning: Enables rapid deployment of CV solutions for niche applications or rapidly evolving requirements where extensive labeled data is unavailable. Imagine classifying rare disease images with only a few examples or identifying new product types on a factory floor without retraining.

- Enhanced Robustness & Generalization: FMs often exhibit better generalization capabilities and robustness to distribution shifts, making them more reliable in real-world, varied environments.

- Creative AI & Content Generation: Revolutionizing industries like marketing, entertainment, and design through text-to-image generation, style transfer, and intelligent image editing.

- Foundation for Robotics & Embodied AI: Providing robots with a general understanding of their visual environment, crucial for complex navigation, object manipulation, and human-robot interaction.

- Democratization of Advanced CV: By offering powerful, pre-trained models, FMs lower the barrier to entry for developers and researchers, accelerating innovation across various domains.

- Accessibility: Generating image descriptions for visually impaired users, making digital content more accessible.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their immense promise, Foundation Models present significant challenges:

- Computational Cost: Training and even inferencing these massive models require immense computational resources, limiting access for smaller organizations and raising environmental concerns.

- Bias and Fairness: FMs learn from vast internet data, which often contains societal biases. These biases can be amplified and propagated by the models, leading to unfair or discriminatory outcomes in applications like facial recognition or content moderation.

- Interpretability and Explainability: Understanding why these black-box models make certain decisions remains a significant challenge, hindering trust and debugging.

- Ethical Implications: The power of generative models raises concerns about misinformation, deepfakes, copyright issues, and the potential for misuse. Responsible AI development and governance are paramount.

- Data Governance: Managing and curating the massive datasets required for FMs, especially with privacy and intellectual property concerns, is a complex task.

- Towards AGI: FMs are a significant step towards general artificial intelligence, demonstrating emergent capabilities and multimodal reasoning. Future research will focus on improving their reasoning, long-term memory, and ability to interact with the physical world.

- Efficiency: Ongoing research aims to develop more efficient architectures, training methods, and deployment strategies to make FMs more accessible and sustainable.

Conclusion

Foundation Models are reshaping the landscape of computer vision, ushering in an era of general-purpose visual intelligence. From the architectural prowess of Vision Transformers to the label-free learning of self-supervised methods and the groundbreaking fusion of vision and language, these models offer unprecedented capabilities. They promise to reduce development friction, unlock novel applications, and democratize access to advanced AI. However, their power comes with a responsibility to address critical challenges related to computational cost, bias, interpretability, and ethical implications. As researchers continue to push the boundaries, Foundation Models for computer vision are poised to drive the next wave of innovation, transforming how we perceive, interact with, and create visual content in the digital world.