Vision Transformers: The Next Revolution in Computer Vision and AI Foundation Models

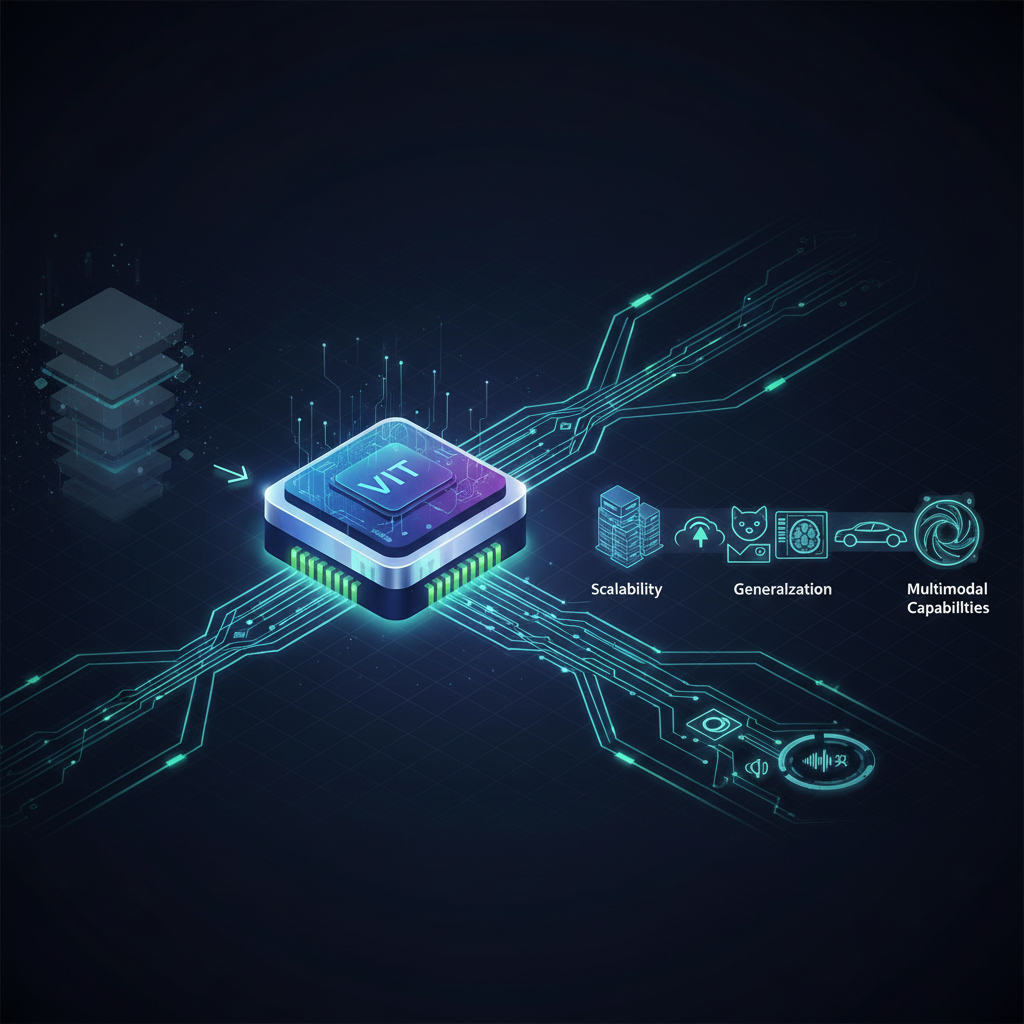

Explore the paradigm shift in computer vision driven by Vision Transformers (ViTs) and foundation models. This article delves into how ViTs are redefining visual understanding, offering unprecedented scalability, generalization, and multimodal capabilities, moving beyond traditional CNNs.

The landscape of artificial intelligence is in a constant state of flux, with breakthroughs regularly redefining what's possible. In recent years, the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) was dramatically reshaped by Large Language Models (LLMs) and the Transformer architecture. Now, a similar, equally profound revolution is unfolding in computer vision: the era of Vision Transformers (ViTs) and the broader concept of foundation models for visual understanding. This paradigm shift is not merely an incremental improvement; it's a fundamental rethinking of how we build intelligent vision systems, promising unprecedented scalability, generalization, and multimodal capabilities.

For decades, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) reigned supreme in computer vision, leveraging their inductive biases like translation equivariance and local connectivity to excel at tasks from image classification to object detection. However, their architectural constraints, while beneficial for certain problems, also limited their ability to capture long-range dependencies and scale effectively with truly massive datasets without significant architectural modifications. Enter the Transformer, an architecture originally designed for sequential data like text, which has now proven its mettle in the visual domain, challenging the long-held dominance of CNNs and ushering in a new age of vision models.

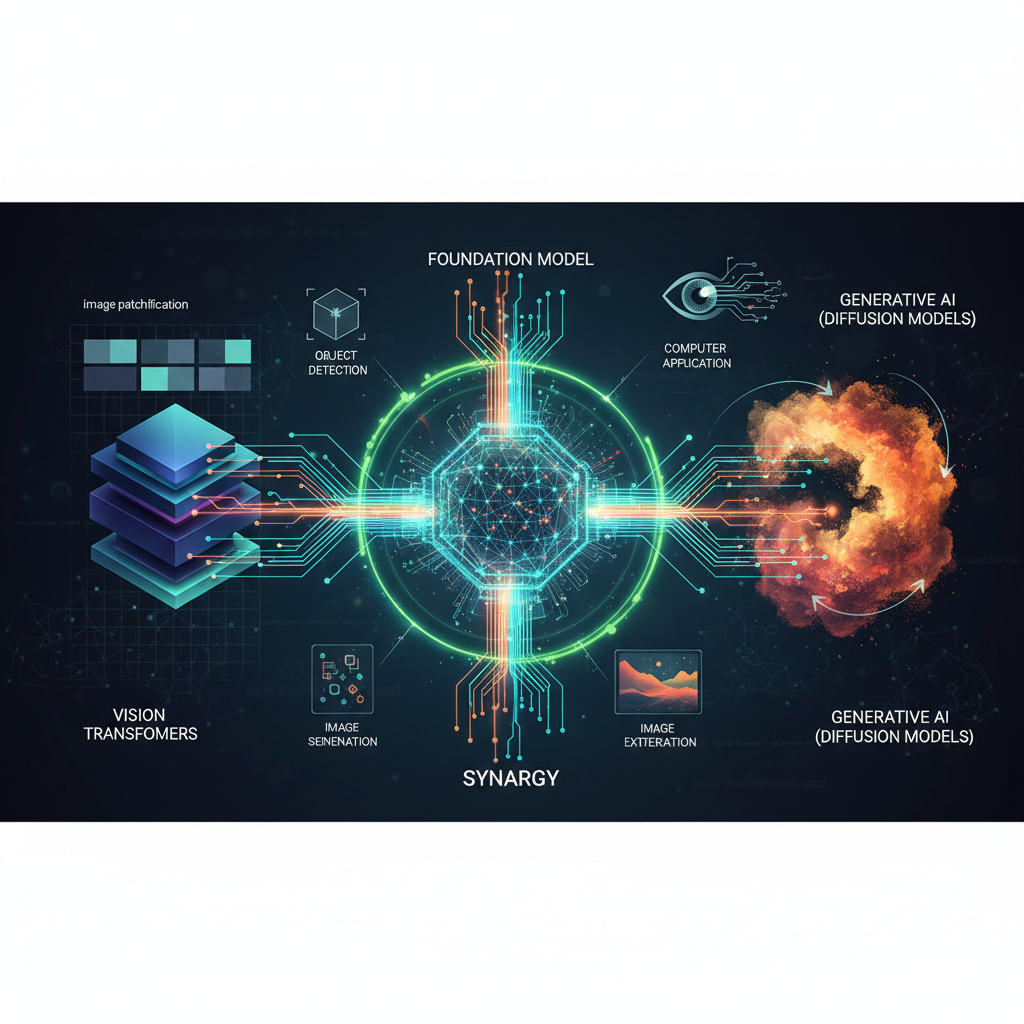

The Genesis: Vision Transformers (ViT)

The journey into foundation models for computer vision truly began with the introduction of the Vision Transformer (ViT) in 2020. Before ViT, applying Transformers to images typically involved combining them with CNNs, using CNNs to extract features which were then processed by Transformers. ViT boldly proposed a different approach: what if we could apply the Transformer architecture directly to images, with minimal modifications?

The core idea behind ViT is surprisingly elegant: treat an image as a sequence of patches, much like a sentence is a sequence of words.

- Image Patching: An input image is first divided into a fixed number of non-overlapping square patches (e.g., 16x16 pixels).

- Linear Embedding: Each 2D patch is then flattened into a 1D vector and linearly projected into a higher-dimensional embedding space. This creates a sequence of patch embeddings.

- Positional Embeddings: Since Transformers inherently lack positional information (unlike CNNs which have spatial awareness built-in), learnable positional embeddings are added to each patch embedding. This allows the model to understand the spatial arrangement of the patches.

- Transformer Encoder: These combined embeddings (patch + positional) are then fed into a standard Transformer encoder. The encoder consists of multiple layers, each containing a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward network. The self-attention mechanism is crucial here, allowing each patch to attend to every other patch in the image, capturing global dependencies across the entire image.

- Classification Head: For classification tasks, a special learnable "classification token" (similar to the

[CLS]token in BERT for NLP) is prepended to the sequence of patch embeddings. The output corresponding to this token at the Transformer encoder's final layer is then passed through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) head to predict the class label.

The breakthrough moment for ViT was demonstrating that, when pre-trained on sufficiently large datasets (like JFT-300M with 300 million images), it could outperform state-of-the-art CNNs on image classification benchmarks like ImageNet. This was a monumental finding, as it showed that the inductive biases of CNNs were not strictly necessary for top performance, especially when vast amounts of data were available. However, ViTs trained on smaller datasets often underperformed CNNs, highlighting their need for extensive pre-training.

The Power of Unlabeled Data: Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) for ViTs

The initial success of ViTs came with a caveat: they required massive supervised datasets for pre-training. This dependency on labeled data is a significant bottleneck, as creating such datasets is expensive, time-consuming, and often prone to bias. This is where Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) emerged as a game-changer for ViTs, enabling them to learn powerful representations from unlabeled data. SSL methods create supervisory signals from the data itself, often by defining a "pretext task."

Key SSL Approaches for Vision Transformers:

-

Masked Autoencoders (MAE): Introduced by Meta AI, MAE is a highly effective and conceptually simple SSL approach. Inspired by BERT's masked language modeling, MAE works by:

- Masking: A large portion (e.g., 75%) of the image patches are randomly masked out.

- Encoding: Only the visible, unmasked patches are fed into an asymmetric encoder (e.g., a ViT encoder). This makes the encoder process only a small fraction of the input tokens, significantly improving computational efficiency.

- Decoding: A lightweight decoder (e.g., a few Transformer layers) then attempts to reconstruct the original pixel values of all patches, including the masked ones, from the encoded visible patches.

- Learning Rich Representations: To successfully reconstruct the missing pixels, the model is forced to learn rich, high-level semantic understanding of the image content and context. MAE has shown remarkable performance, often achieving state-of-the-art results with less pre-training data than other SSL methods.

Example: Imagine an image of a cat. MAE might mask out the cat's head and paws. To reconstruct these, the model needs to understand not just the fur texture from the visible body, but also the overall structure of a cat, its typical pose, and how its parts relate to each other.

-

Contrastive Learning: Methods like DINO, MoCo v3, SimCLR, and BYOL have also been adapted for ViTs. The general idea is to learn representations by:

- Augmenting: Creating multiple augmented views of the same image (e.g., cropping, color jittering, rotation).

- Contrasting: Encouraging the model to learn similar embeddings for different augmented views of the same image (positive pairs) while pushing apart embeddings of different images (negative pairs).

- Emergent Properties: Interestingly, some contrastive learning methods like DINO have shown an emergent property where the self-attention maps of the ViT spontaneously segment objects within an image without any explicit segmentation supervision. This highlights the powerful, semantic representations these models learn.

Example: If you have an image of a dog, you create two different cropped and color-shifted versions. The model learns to produce similar numerical representations for both versions, while ensuring these representations are distinct from those of an image of a car.

SSL has been pivotal in democratizing ViTs, allowing researchers and practitioners to leverage massive amounts of unlabeled data to pre-train powerful foundation models, which can then be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks with significantly less labeled data.

Bridging the Gap: Hierarchical Vision Transformers

While pure ViTs excel at capturing global dependencies, their uniform patch processing can be computationally expensive for high-resolution images and might not be ideal for dense prediction tasks like semantic segmentation or object detection, which traditionally benefit from hierarchical feature extraction (like the feature pyramids in CNNs). This led to the development of Hierarchical Vision Transformers.

-

Swin Transformer: One of the most prominent hierarchical ViTs is the Swin Transformer ("Shifted Window Transformer"). Swin addresses the limitations of pure ViTs by:

- Hierarchical Feature Maps: It constructs hierarchical feature maps by merging image patches in deeper layers, creating multi-scale representations.

- Shifted Windows: Instead of global self-attention across all patches, Swin performs self-attention within local, non-overlapping windows. To allow for cross-window connections and capture global information, it introduces a "shifted window" mechanism in alternating layers. This dramatically reduces computational complexity while still enabling long-range interactions.

- Performance: Swin Transformer has achieved state-of-the-art results across a wide range of vision tasks, including image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation, proving that hierarchical processing can be effectively integrated into the Transformer architecture.

Example: In the early layers, a Swin Transformer might analyze small 4x4 pixel windows. As it goes deeper, it merges these into larger 8x8 or 16x16 windows, allowing it to understand both fine-grained details and broader contextual information.

-

Pyramid Vision Transformer (PVT): Another notable hierarchical ViT, PVT, also aims to generate pyramid-like feature maps. It achieves this by progressively reducing the resolution of the patch embeddings as they pass through the Transformer layers, allowing for efficient processing of high-resolution inputs and better performance on dense prediction tasks.

These hierarchical designs combine the best of both worlds: the global reasoning capabilities of Transformers and the multi-scale, efficient processing traditionally associated with CNNs, making them highly versatile for a broad spectrum of computer vision applications.

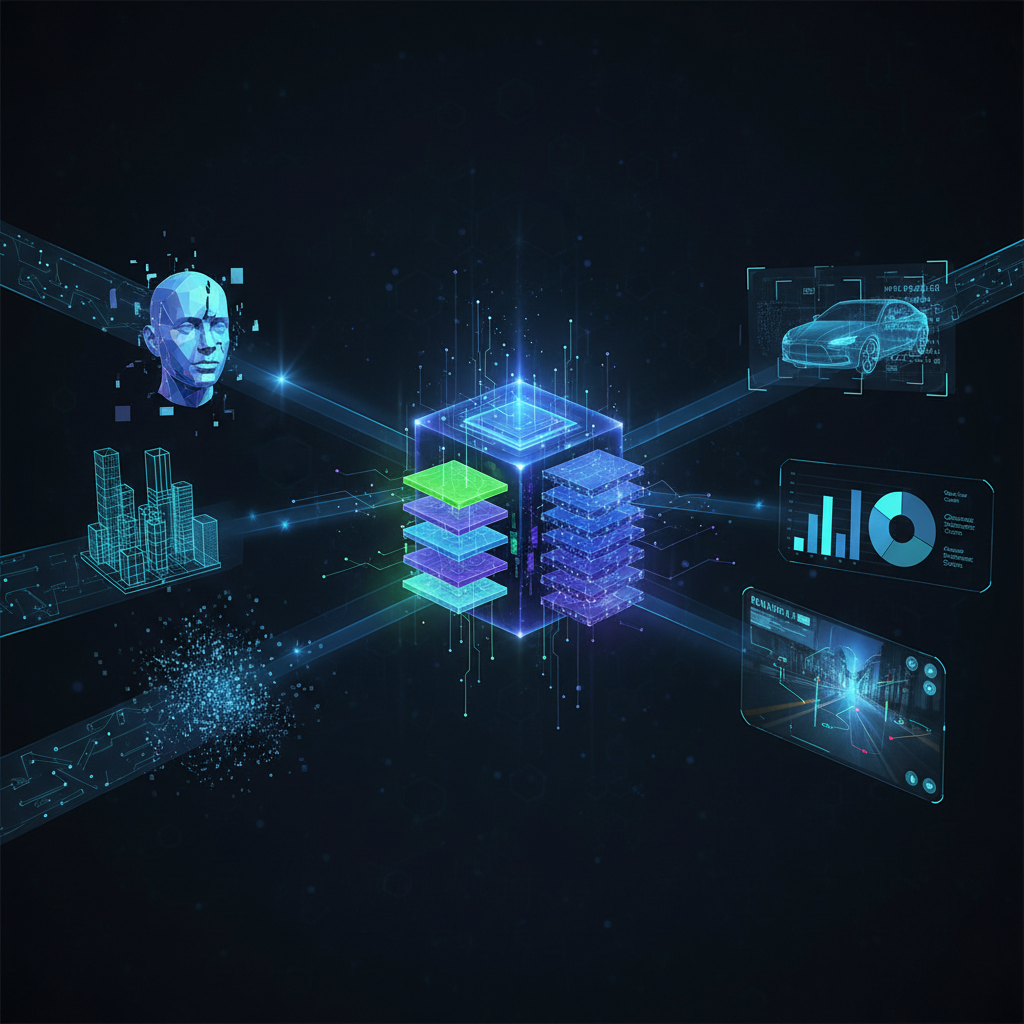

Beyond Vision: Multimodal Foundation Models (Image-Text Integration)

Perhaps one of the most exciting frontiers in foundation models is the integration of different modalities, particularly vision and language. These multimodal foundation models learn joint representations of images and text, enabling unprecedented capabilities like open-vocabulary understanding and intuitive human-AI interaction.

-

CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training): Developed by OpenAI, CLIP is a groundbreaking model that learns robust visual representations by training on a massive dataset of 400 million image-text pairs collected from the internet.

- Mechanism: CLIP uses a contrastive learning approach. It trains an image encoder (a ViT or ResNet) and a text encoder (a Transformer) simultaneously. The goal is to maximize the cosine similarity between the embeddings of an image and its corresponding text caption, while minimizing similarity with non-matching image-text pairs.

- Zero-Shot Transfer: The power of CLIP lies in its zero-shot transfer capability. Once trained, it can perform classification on unseen categories without any fine-tuning. For example, to classify an image, you simply provide text prompts like "a photo of a cat," "a photo of a dog," "a photo of a bird," etc. The model then predicts the class whose text embedding is most similar to the image embedding. This allows for highly flexible and adaptable vision systems.

Example: You can ask CLIP to identify "a picture of a vintage car" or "a picture of a healthy plant" even if it hasn't seen specific examples of vintage cars or healthy plants during training, as long as it has learned general concepts of "vintage," "car," "healthy," and "plant" from its vast pre-training data.

-

DALL-E 2 / Stable Diffusion: While primarily generative models, these systems are built upon powerful image-text foundation models (often leveraging variations of Transformers and diffusion models) that understand the intricate relationship between text prompts and visual concepts. They showcase the ability to generate highly realistic and diverse images from natural language descriptions, demonstrating a deep multimodal understanding.

-

OWL-ViT (Open-Vocabulary Object Detection with Vision Transformers): Building on the success of CLIP, OWL-ViT extends open-vocabulary capabilities to object detection. It allows users to detect arbitrary objects in an image by providing natural language queries (e.g., "detect all instances of a red car" or "find the person wearing glasses"). This eliminates the need to pre-define and train for every possible object category, revolutionizing object detection for novel scenarios.

These multimodal models represent a significant step towards more general-purpose AI, where systems can understand and interact with the world through both visual and linguistic cues, leading to more intuitive and powerful applications.

Practical Applications and Future Directions

The implications of foundation models for computer vision are vast and are already reshaping various industries:

- Zero-shot/Few-shot Learning: This capability drastically reduces the need for large, task-specific labeled datasets. Businesses can deploy vision models much faster for new products or services, even with limited data. For instance, a retail company can quickly set up a system to identify a new product line without collecting thousands of labeled images.

- Open-Vocabulary Tasks: This enables unprecedented flexibility. In security, a system could detect "unattended luggage" or "a person wearing a suspicious backpack" without explicit training for these specific items or scenarios. In quality control, it could identify "defective components" based on a textual description of the defect.

- Robotics: Foundation models enhance robotic perception, allowing robots to identify and interact with novel objects in unstructured environments. A robot could be instructed to "pick up the blue cup" or "avoid the fragile item" using natural language, enabling more adaptable and intelligent robotic systems.

- Medical Imaging: Robust pre-trained models can be fine-tuned with smaller, specialized medical datasets to assist in diagnosis, anomaly detection, and surgical planning, potentially accelerating research and improving patient outcomes. Their ability to generalize can make them more robust to variations in medical scans.

- Autonomous Driving: Improved object recognition, scene understanding, and multimodal fusion (e.g., combining camera feeds with LiDAR and radar data) are critical for safer and more reliable self-driving vehicles. Foundation models can help identify unusual road conditions or unexpected obstacles.

- Content Creation and Moderation: Generating images from text (like DALL-E 2) opens new avenues for creative industries. In content moderation, models can identify inappropriate visual content based on complex textual policies.

- Accessibility: Multimodal models can provide richer descriptions of images for visually impaired users, translating visual information into detailed textual explanations.

Future Directions:

- Efficiency and Deployment: The large size of these models poses challenges for deployment on edge devices or in real-time applications. Research is actively exploring techniques like model distillation, quantization, sparse attention mechanisms, and efficient architectures to make these powerful models more accessible and practical.

- Interpretability and Explainability: Understanding why a foundation model makes a certain prediction is crucial, especially in high-stakes domains like healthcare or autonomous driving. Developing methods to interpret the internal workings of these complex models remains an active research area.

- Ethical Considerations: The vast datasets used for pre-training can embed societal biases, leading to unfair or discriminatory outcomes. Addressing bias, ensuring fairness, and preventing misuse are critical ethical challenges that require ongoing attention and mitigation strategies.

- Unified Multimodal Models: The trend is moving towards even more integrated multimodal models that can seamlessly process and generate information across various modalities (vision, language, audio, sensor data) in a truly unified manner, mimicking human perception and cognition.

- Reasoning and Embodiment: Future foundation models will likely move beyond pure perception to incorporate more complex reasoning capabilities and integrate with embodied agents (robots) to learn through interaction with the physical world.

Why This Matters for AI Practitioners and Enthusiasts

For anyone involved in AI, understanding foundation models for computer vision is no longer optional; it's essential.

- Staying Cutting-Edge: These models represent the current state-of-the-art and are rapidly becoming the backbone of advanced computer vision solutions.

- Architectural Evolution: It signifies a fundamental shift away from purely CNN-centric thinking, encouraging a broader perspective on model design.

- Leveraging Existing Tools: Frameworks like Hugging Face's Transformers library and

timm(PyTorch Image Models) provide easy access to pre-trained ViTs and other foundation models, allowing practitioners to fine-tune them for custom tasks with relatively little effort. - Unlocking New Possibilities: The zero-shot, few-shot, and open-vocabulary capabilities empower developers to tackle problems that were previously intractable due to data scarcity or the need for constant re-training.

- Research and Innovation: The field is incredibly dynamic, offering fertile ground for new research in areas like efficiency, multimodal integration, interpretability, and novel applications.

The era of Vision Transformers and foundation models marks a pivotal moment in computer vision. By moving towards more general-purpose, scalable, and data-efficient architectures, we are building vision systems that are not only more powerful but also more adaptable and capable of understanding the world in a way that brings us closer to true artificial intelligence. The journey has just begun, and the future promises even more exciting breakthroughs.