Generative AI: Revolutionizing Scientific Discovery and Innovation

Explore how Generative AI, beyond LLMs and Diffusion Models, is transforming scientific advancement. Discover its potential to accelerate the design of novel molecules, proteins, and materials, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error methods.

The world of science has always been driven by discovery – the relentless pursuit of understanding, innovation, and solutions to humanity's most pressing challenges. From the synthesis of life-saving drugs to the creation of revolutionary materials, the pace of scientific advancement has historically been constrained by the limits of human intuition, experimental capacity, and computational power. But what if we could accelerate this process by orders of magnitude? What if we could design novel molecules, proteins, and materials not through laborious trial-and-error, but through intelligent, data-driven generation?

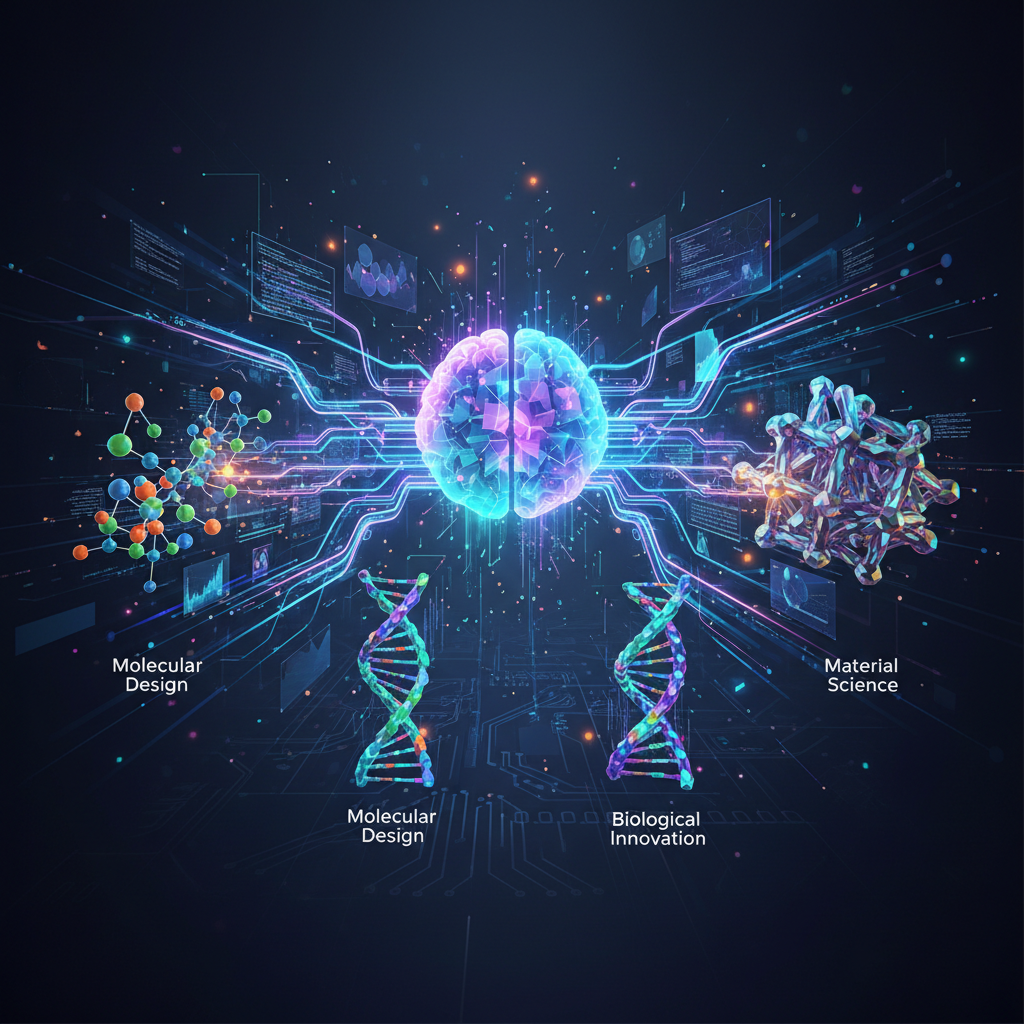

Enter Generative AI. While Large Language Models (LLMs) and Diffusion Models have captured public imagination with their ability to create text, images, and audio, their true transformative potential extends far beyond creative tasks. The next frontier is applying these powerful generative capabilities to the highly structured, complex, and information-rich domains of scientific data. This isn't just about predicting outcomes; it's about inventing the building blocks of future science. This burgeoning field, at the nexus of AI, chemistry, biology, and materials science, promises to redefine how we approach scientific discovery, particularly in the critical area of drug design.

The Grand Challenge: Why Generative AI is a Game-Changer

Scientific discovery, especially in fields like drug development, is notoriously slow, expensive, and often fraught with failure. A typical drug discovery pipeline can take over a decade and cost billions of dollars, with a high attrition rate. This is largely due to:

- Vast Search Spaces: The chemical space of potential drug-like molecules is estimated to be astronomically large (10^60 to 10^100), making exhaustive experimental screening impossible.

- Complex Interactions: Predicting how a molecule will interact with a biological target, its ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties, and its overall efficacy and safety is incredibly challenging.

- Reliance on Human Intuition: While invaluable, human intuition alone struggles to navigate the high-dimensional data landscapes involved in designing novel compounds or materials.

Generative AI offers a paradigm shift. Instead of screening existing libraries or making incremental modifications, it empowers us to design from scratch (de novo) entirely new entities – molecules, proteins, or materials – that are optimized for desired properties. This promises to drastically reduce discovery timelines, lower costs, and unlock previously inaccessible solutions.

De Novo Molecular Design: Crafting Molecules from Scratch

The cornerstone of drug discovery is finding molecules that can modulate biological processes. Traditionally, this involved screening vast libraries of existing compounds. Generative AI flips this on its head, aiming to create novel molecules with specific, pre-defined characteristics.

The Core Challenge: Representing and Generating Molecules

Molecules are complex entities. They can be represented as:

- SMILES strings: A linear text-based notation (e.g.,

CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)Ofor Aspirin). - Molecular graphs: Where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- 3D coordinates: Describing the spatial arrangement of atoms.

Generative models must not only produce novel structures but also ensure they are chemically valid, synthesizable, and possess the desired biological or physical properties.

Recent Developments and Architectures:

-

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) with Generative Capabilities:

- GNNs are particularly well-suited for molecular data because they naturally operate on graph structures. Generative GNNs learn to construct molecular graphs atom-by-atom or bond-by-bond.

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): Models like GraphVAE encode a molecular graph into a continuous latent space and then decode from this space to generate new graphs. By sampling from different points in the latent space, novel molecules can be generated. The encoder learns a probabilistic mapping, allowing for smooth interpolation and generation of diverse structures.

- Flow-based Models: These models learn a sequence of invertible transformations to map simple latent distributions to complex data distributions. For molecules, they can generate structures by iteratively adding atoms and bonds, ensuring chemical validity at each step.

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): While challenging to apply directly to discrete graph structures, some GAN variants use GNNs as generators and discriminators to learn to produce realistic molecular graphs.

-

Diffusion Models for Molecules:

- Inspired by their success in image generation, diffusion models are now being adapted for molecular structures. They work by iteratively denoising a random input (e.g., a noisy molecular graph or 3D conformation) until a coherent structure emerges.

- These models show immense promise in generating diverse and novel structures, including 3D molecular conformations, which are crucial for understanding drug-target interactions. They can learn the complex distribution of valid chemical structures and generate high-quality samples.

-

Reinforcement Learning (RL) for Optimization:

- Generative models can be combined with RL to navigate the vast chemical space more effectively. An RL agent learns a policy to generate molecules, receiving a "reward" based on how well the generated molecule satisfies desired properties (e.g., high binding affinity predicted by a separate model, low toxicity).

- Example: A generative model proposes a molecule, a property predictor (e.g., a GNN-based binding affinity predictor) evaluates it, and this score is used as a reward signal to train the generative model to produce better molecules over time. This creates a powerful feedback loop for optimization.

-

Conditional Generation:

- A key advancement is the ability to generate molecules conditioned on specific criteria. This means we can ask the model to generate molecules that not only have certain ADMET properties (e.g., high solubility, low toxicity) but also bind specifically to a particular protein target.

- This often involves integrating information about the target protein's structure or sequence into the generative model's input or reward function.

Practical Example: Designing a Novel Kinase Inhibitor Imagine we want to design a new drug to inhibit a specific kinase enzyme implicated in cancer.

- Define Properties: We'd specify desired properties: high binding affinity to the target kinase, good oral bioavailability, low predicted toxicity, and a molecular weight within a drug-like range.

- Train Generative Model: A GNN-based VAE or a diffusion model is trained on a vast dataset of known molecules.

- Conditional Generation/RL: We then use conditional generation (e.g., by providing features of the kinase binding pocket) or an RL framework where the reward function incorporates predictions from a pre-trained binding affinity model and ADMET predictors.

- Iterative Refinement: The model generates candidate molecules. These are then computationally screened, and the best candidates are either synthesized and experimentally tested, or their properties are fed back to the model for further refinement.

Protein Design and Engineering: Building Life's Machinery

Proteins are the workhorses of biology, performing nearly every function in living organisms. Designing new proteins with novel functions (e.g., enzymes, antibodies, therapeutics) or optimizing existing ones is a frontier with enormous potential.

The Challenge: Sequence-Structure-Function Relationship

The 3D structure of a protein dictates its function, and this structure is determined by its amino acid sequence. The "protein folding problem" (predicting structure from sequence) has been largely addressed by models like AlphaFold. Now, the inverse problem – designing a sequence for a desired structure or function – is the focus of generative AI.

Recent Developments:

-

Protein Language Models (pLMs):

- Just as LLMs learn the grammar and semantics of human language, pLMs (e.g., ESMFold, AlphaFold-latest iterations, variations of BERT/GPT for protein sequences) learn the "language" of proteins. They are trained on massive datasets of protein sequences and structures.

- Initially used for structure prediction, pLMs are now being adapted for generating novel protein sequences. By sampling from the learned distribution of sequences, they can propose sequences that are likely to fold into stable structures or exhibit specific functions.

- Example: Given a desired protein family or functional motif, a pLM can generate diverse sequences that are likely to belong to that family or perform that function.

-

Generative Models for Protein Backbones:

- Diffusion models or VAEs can generate novel protein backbone structures (the arrangement of the polypeptide chain in 3D space) directly.

- Once a backbone structure is generated, "sequence design" algorithms (often leveraging pLMs or inverse folding methods) are used to determine the amino acid sequence that would stabilize that specific backbone.

-

Inverse Protein Folding:

- This is the holy grail: given a desired 3D protein structure (e.g., a binding pocket for a specific drug), generate the amino acid sequence that would fold into that exact structure.

- Models are being developed that take a target 3D structure as input and output a probability distribution over amino acid sequences, allowing for the design of sequences that are likely to adopt the desired fold.

Practical Example: Designing a Novel Enzyme for Biocatalysis Imagine we need an enzyme that can perform a specific chemical reaction not efficiently catalyzed by natural enzymes.

- Define Function/Structure: We might specify a desired active site geometry or a known scaffold that performs a similar reaction.

- Generative Design: A generative model (e.g., a diffusion model for backbones followed by a pLM for sequence design) proposes novel protein sequences.

- Computational Validation: The generated sequences are then run through protein folding predictors (like AlphaFold) to check if they adopt the desired 3D structure. Molecular dynamics simulations can further assess stability and catalytic activity.

- Experimental Synthesis: Promising candidates are synthesized and experimentally tested for their enzymatic activity.

Reaction Pathway Prediction and Synthesis Planning: Automating Chemical Synthesis

Beyond designing molecules, generative AI is revolutionizing how we make them. Chemical synthesis is a complex art, often requiring extensive expert knowledge to devise multi-step reaction pathways.

The Challenge: Navigating Chemical Reactivity

Predicting how molecules will react (forward reaction) and, more critically, working backward from a target molecule to its precursors (retrosynthesis) are computationally intensive and require deep chemical understanding.

Recent Developments:

-

Retrosynthesis AI:

- Generative models, often sequence-to-sequence (treating SMILES strings as sequences) or graph-to-graph models, are trained on vast databases of known chemical reactions.

- Given a target molecule, these models predict plausible precursor molecules and the reactions needed to form the target. This effectively automates the process of retrosynthesis planning, suggesting multiple synthetic routes.

- Example: A model might suggest that a complex molecule could be formed by coupling two simpler fragments, and then recursively suggest precursors for those fragments, building a full synthetic tree.

-

Forward Reaction Prediction:

- Conversely, models can predict the products of a given set of reactants and reaction conditions. This is crucial for optimizing reaction conditions and understanding reaction mechanisms.

-

AI-driven Robotic Synthesis:

- The ultimate vision is to integrate these generative planning tools with automated laboratory systems. AI designs the molecule and its synthetic route, and then robotic platforms execute the synthesis autonomously. This "self-driving lab" concept promises to dramatically accelerate chemical discovery and production.

Practical Example: Synthesizing a New Pharmaceutical Intermediate A pharmaceutical company needs to synthesize a complex intermediate for a new drug candidate.

- Input Target: The SMILES string or molecular graph of the target intermediate is fed into a retrosynthesis AI.

- Generate Pathways: The AI generates several potential synthetic pathways, ranking them by predicted feasibility, cost, and number of steps.

- Optimization: Chemists review the pathways, and the AI can be prompted to explore variations or optimize for specific criteria (e.g., using readily available starting materials).

- Automated Execution: The selected pathway is then programmed into an automated synthesis robot, which executes the reactions, purification, and characterization steps.

Materials Discovery: Engineering the Future of Matter

The properties of materials underpin every aspect of modern technology, from semiconductors to batteries to aerospace components. Generative AI is now being used to design new materials with tailored properties.

The Challenge: Infinite Combinations of Elements and Structures

Designing new materials involves exploring vast combinations of elements, crystal structures, and microstructures, each yielding unique properties. Traditional methods rely heavily on experimental screening and intuition.

Recent Developments:

-

Generative Models for Crystal Structures:

- GNNs and diffusion models are being used to generate novel crystal structures. These models learn the rules governing stable crystal packing and can propose new arrangements of atoms.

- These generated structures can then be fed into physics-based simulations (e.g., Density Functional Theory, DFT) to predict their properties (e.g., electronic band gap, mechanical strength, superconductivity).

- Example: Designing a new thermoelectric material by generating crystal structures that exhibit both low thermal conductivity and high electrical conductivity.

-

Polymer Design:

- Generative models can design novel polymer architectures (e.g., monomer sequences, branching patterns) to achieve desired bulk properties like flexibility, degradation rate, or strength.

Practical Example: Discovering a New Catalyst for CO2 Conversion To combat climate change, we need highly efficient catalysts to convert CO2 into useful chemicals.

- Define Properties: We specify desired catalytic activity, stability, and selectivity for CO2 conversion.

- Generative Design: A generative model for crystal structures proposes novel metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) or other porous materials.

- High-Throughput Simulation: The generated structures are computationally screened using DFT or other quantum chemistry methods to predict their catalytic activity for CO2 reduction.

- Synthesis and Testing: The most promising candidates are synthesized and experimentally validated in the lab.

Practical Insights & Opportunities for AI Practitioners

For AI practitioners and enthusiasts looking to contribute to this exciting field, several key areas demand attention:

- Model Architectures: A deep understanding of GNNs, VAEs, GANs, and especially Diffusion Models is crucial. Learn how these models are adapted for discrete, structured data (graphs, sequences) rather than continuous data (images, text).

- Data Representation: Mastering how scientific data (SMILES, molecular graphs, 3D coordinates, protein sequences, crystal lattices) is encoded and decoded for ML models is fundamental. Tools like RDKit and OpenBabel are indispensable.

- Evaluation Metrics: Beyond standard ML metrics (accuracy, precision), domain-specific metrics are vital. For molecules, this includes Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED), Synthetic Accessibility (SA) score, diversity, novelty, and target-specific binding scores. For proteins, stability, solubility, and functional activity are key.

- Computational Chemistry Tools: Familiarity with simulation tools (e.g., molecular dynamics, DFT) is essential for generating ground truth data, validating model outputs, and predicting properties.

- Ethical Considerations: The power of generative AI in science comes with responsibility. Addressing potential biases in generated outputs, ensuring safety (e.g., avoiding generation of toxic compounds), and promoting responsible use are paramount.

- Hardware and Infrastructure: Training these complex models on vast scientific datasets requires significant computational resources, often leveraging GPUs, TPUs, and cloud computing platforms.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: This field thrives on collaboration. AI researchers must work closely with chemists, biologists, materials scientists, and pharmacologists to define problems, interpret results, and ensure scientific validity.

Emerging Trends: The Future is Autonomous

The field is evolving rapidly, with several exciting trends shaping its future:

- Foundation Models for Science: The vision of training massive, general-purpose generative models on all available scientific data (all known molecules, proteins, reactions, materials) that can then be fine-tuned for specific tasks. This parallels the success of LLMs in natural language.

- Multi-modal Generative AI: Integrating information from diverse sources – scientific literature (text), microscopy images, experimental data, and structured molecular data – to inform and condition generative processes.

- Active Learning & Closed-Loop Discovery: Generative models propose experiments, experimental results are fed back to refine the models, creating an autonomous, self-optimizing discovery cycle. This "AI-driven laboratory" could dramatically accelerate the pace of discovery.

- Explainable AI (XAI) for Generative Design: Understanding why a model generated a particular molecule or protein is critical for scientific trust, validation, and gaining new scientific insights. XAI methods are being developed to shed light on the black box of generative models.

Conclusion

Generative AI for scientific discovery and drug design represents a profound leap forward, moving beyond mere data analysis to actively create the building blocks of scientific progress. From designing novel drugs to combat intractable diseases, to engineering proteins with unprecedented functions, to discovering materials that will power future technologies, the potential impact is staggering. This is a field where cutting-edge machine learning meets grand scientific challenges, offering immense opportunities for innovation, collaboration, and ultimately, for solving some of humanity's most pressing problems. For AI practitioners and enthusiasts, engaging with this domain means not just pushing the boundaries of AI, but also contributing directly to a future shaped by intelligent discovery.